“Jessica” is seven-and-a-half minutes of light and love — what producer Johnny Sandlin called “the happiest song I’ve ever heard.” The instrumental surfaced at an intensely turbulent time for the Allman Brothers Band, which was reeling from the deaths of two founding members and struggling with drug addiction. That didn’t stop guitarist Dickey Betts from composing a paean to bright-eyed innocence, its jaunty melody inspired by (and named after) his infant daughter. “Jessica” may have performed tepidly on on the charts, but constant FM radio airplay (and its role as the opening theme to Britain’s popular motoring show Top Gear) ensured its status as one of the Allmans’ defining compositions — an aural representation of unbridled positivity, hatched in its lingering vacancy.

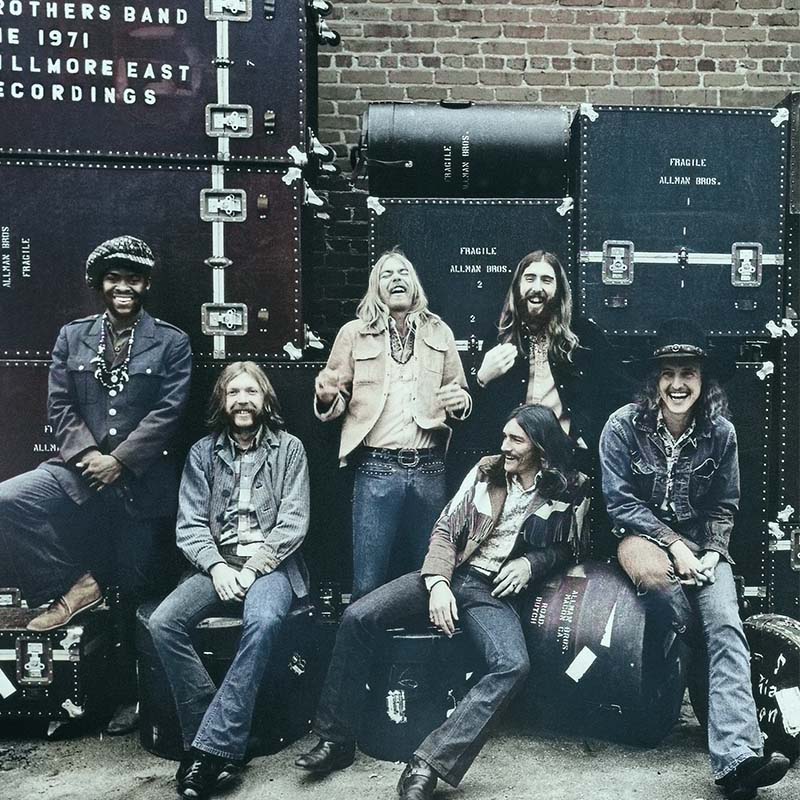

Duane Allman’s sudden death in an October 1971 motorcycle accident in western Macon, Ga. sent shockwaves through the Allman organization. Besides the permanent loss of the band’s founder and musical visionary (not to mention singer/keyboardist Gregg Allman’s beloved older sibling), it also meant an integral part of their twin-guitar sound was gone for good, raising anxieties inside and outside the group about their commercial prospects. After weeks of mourning, the Allmans rallied, aiming to capitalize on their reputation as a live act — a reputation cemented by the release of the landmark At Fillmore East, recorded in New York City just six months prior to Duane’s death — and prepare a fitting follow-up.

The resulting double LP, 1972’s Eat a Peach, combined unreleased material from the Allman Brothers Band’s multiple Fillmore sets (including a 33-minute “Mountain Jam” that took up all of Sides B and D) alongside a handful of new songs, including now-classics like “Melissa” and “Blue Sky.” Several of the album’s songs, including the Gregg Allman-penned “Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More” and the nine-minute “Les Brers in A Minor,” were openly dedicated to Duane. Warner Bros. imprint Capricorn Records savvily marketed Eat a Peach for the price of a single LP, and combined with Capricorn Vice President of Promotions Dick Wooley’s decision to broadcast the band’s New Year’s Eve 1971 performance in New Orleans across multiple radio stations, the record took off, eventually selling even more units than At Fillmore East. Reports of the Allman Brothers Band’s demise, it turned out, were greatly exaggerated.

Those reports weren’t unwarranted, however. Duane Allman’s absence instilled both a power vacuum and a sense of directionlessness within the remaining members of the Allman Brothers Band, each of whom was addicted to illicit substances. Betts reluctantly took the reins, and a five-piece incarnation of the band departed on a 90-stop tour to promote Eat a Peach. At the same time, the Allmans used a large chunk of their earnings to purchase a new homebase: an 18-room Tudor Revival on 432 acres of land north of Macon in Juliette, Ga., a site they dubbed “The Farm” and where they would compose and rehearse their next record, Brothers and Sisters. The driving force behind The Farm was bassist Berry Oakley, who had always dreamed of constructing a community around the Allman organization. Embedded in the purchase also lay a latent hope that the new surroundings would revitalize the group’s rapport and help them begin to move past the pain of Duane’s death.

Yet while The Farm fulfilled Oakley’s dreams, its curative powers didn’t work on him for long. According to roadie Kim Payne in Alan Paul’s One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band, “Everything Berry had envisioned for everybody — including the crew, the women and children — was shattered on the day Duane died, and he didn’t care after that.” Oakley leaned even harder into drugs and alcohol to soothe his grief, and developed a dependence that severely hampered his ability to perform. Seemingly the only development that rejuvenated Oakley’s spirits was the addition of pianist Chuck Leavell, the Allman Brothers Band’s first hire after Duane’s death. Leavell joined the group after collaborating with Gregg Allman on his first solo LP, 1973’s Sandlin-produced Laid Back, and Oakley worked hard to ensure the pianist felt comfortable in his new surroundings.

Then, just over a year after Duane Allman’s death, Oakley suffered his own motorcycle mishap three blocks from the site of Duane’s accident. Heroin-addled yet excited to lead a giant jam session, Oakley crashed his 1967 Triumph into a bus and fractured his skull. He initially declined a trip to the hospital and returned home, where he slowly suffered from traumatic brain injuries until he consented to treatment. By then it was too late, and 45 minutes later, Oakley died in a hospital bed at the age of 24.

If Duane’s death had thrown the band into extreme turbulence, Oakley’s death felt like another hard thump in the air. The only upside was that the band were more prepared to deal with it. Though they stubbornly insisted against replacing Duane, they quickly added bassist Lamar Williams and continued the Capricorn Sound studio sessions for Brothers and Sisters. On the whole, the album is defined by songs like the searing “Ramblin’ Man” (the Allmans’ highest-charting single) and the slide showcase “Pony Boy,” tracks that espouse a version of Southern blues-rock that leaned more heavily country under Betts’ leadership. “Jessica,” which opens pure folk via Haight-Ashbury strums, immediately sets itself apart from its brethren: its opening bed of acoustic guitar comes courtesy of Les Dudek, a session guitarist who had previously supplied lead guitar harmonies to “Ramblin’ Man.” When the rest of the band enters four measures in, it’s Leavell’s grand piano that cuts through the mix, harmonically jelling Williams’ bass and Dudek’s strums together to establish a warm, amiable mood — a world of difference from the minor-key rollicking of the rest of Brothers and Sisters.

That buoyant lead guitar melody is the heartbeat of “Jessica,” and that’s not entirely a metaphor: trace the rise and fall of the melody with your finger, and note how it resembles the sinusoidal pulse of an EKG. The part was inspired by the peculiar playing of legendary Romani guitarist Jean “Django” Reinhardt: due to severe burns on his left hand, Reinhardt learned to play his instrument with just his index and middle fingers. Together with violinist Stephané Grappelli, he formed the Quintette du Hot Club de France, a group that invented and propagated ”gypsy jazz,” a variation of continental jazz that emphasized swing rhythms and dense string interplay. In honor of the guitarist, who died two decades prior, Betts designed a lead guitar melody that could be played Reinhardt-style, with just two fingers.

Betts’ notes, however, felt aimless without a visual anchor. “I need to have an image in my head before I can start writing an instrumental, because then it’s too vague,” Betts recalled. He landed on one with the entrance of his blissfully beaming baby daughter, Jessica. “I started playing along, trying to capture musically the way she looked bouncing around the room.” Suddenly inspired, Betts finished the melody and dedicated the song to his infant muse.

Though he’s not credited, Dudek claims to have made significant contributions to “Jessica.” According to Dudek, Betts invited him and his girlfriend over to The Farm for steaks and a session, and when Betts played them the “Jessica” melody, he hit a roadblock and left to check on the food. In his absence, Dudek supplied the bridge part, which drops down to the key of G from the melody’s original A Major, and when Betts returned, he was elated to discover the song had taken a new direction. The two guitarists approached the rest of the band with “Jessica,” and in response they added a piano solo for Leavell and another guitar solo for Betts. Other members of the Allman Brothers Band have disputed Dudek’s insistence that he deserves credit on the composition of “Jessica” by highlighting their own contributions to the completed song, but Dudek claims that Betts himself implored Allmans manager Phil Walden to divide songwriting royalties between the two.

Regardless of the internal dispute over “Jessica” (or perhaps in spite of it), the amicable energy radiating through the song reflects the new iteration of the Allman Brothers Band at its cohesive peak. In fact, you’ll be forgiven for thinking that the harmonies over the lead melody are guitars, given the influence of the iconic Allman-Betts twin guitar sound. Isolate the tracks in KORD, and you’ll discover that it’s actually twin keyboards intertwined with Betts’ lead: Leavell’s Rhodes electric on top and Gregg’s Hammond organ on bottom. Betts’ melodies commonly feature the intertwining of multiple instruments, and yet the pairing of keys and guitar is utterly seamless here. Then again, the tight playing across the entire track demonstrates how, even after the gutting of its lineup, the Allman Brothers Band remained defined by topnotch musicianship. Sandlin’s warm production also heightens the sense of camaraderie among the group, who gamely match the energy of Leavell’s and Betts’ leads like kids playing follow the leader.

Such camaraderie, unfortunately, would not last long. Money and celebrity would contribute — Brothers and Sisters would find success immediately, hitting number one on the Billboard 200 and going gold within two weeks — but even before the album’s release, lingering enmity about band leadership and spiraling drug problems caused fractures within the Allmans camp. These wounds would fester during their next tour, in the summer of 1973. Multiple incidents occurred, from a notorious backstage brawl during a show with the Grateful Dead (spurred on in part by the Dead’s decision to dose the unwitting Allmans with LSD) to an oversold festival show at New York’s Watkins Glen Speedway, where almost 600,000 witnessed a disastrous, drug-dimmed performance that culminated in Betts walking off stage. The Allman Brothers Band may have been playing enormous venues and earning top dollar for their performances, but the glue holding the act threatened to make their accomplishments moot.

By the time Gregg Allman started dating pop icon Cher (leading to a 1975 marriage that lasted all of nine days), the “community” Berry Oakley hoped to foster when he spearheaded the purchase of The Farm had all but fallen apart. Fame and fortune had thrown the Allman Brothers Band’s priorities into disarray, with a focus on sex and drugs trumping their musical obligations. They would get through one more LP (the torturously-recorded Win, Lose, or Draw) before Gregg agreed to testify in a federal drug case involving Scooter Herring, a security guard and friend of the group. Allman’s decision made him persona non grata among his bandmates, finally causing their breakup in 1976.

Yet while the Allman Brothers Band ceased to be, the existence of “Jessica” in the sphere of popular music somehow endured. As Brothers and Sisters’ second single, it failed to reach even the Top 40, but it stayed a staple on the airwaves thanks to a four-minute edit that surfaced right at the time many FM radio stations were transitioning to album-oriented rock (AOR) programming formats. In the interim, the influence of the Allmans’ sound spread far and wide, from the proliferation of Southern rock (e.g., Lynyrd Skynyrd and the Marshall Tucker Band) to the likes of the Irish hard rock band Thin Lizzy, which developed its own powerful and distinctive twin-guitar harmony sound. In 1977, a year after the Allman Brothers Band dissolved, BBC2’s Top Gear aired its first episode, using “Jessica” as its intro song, and as its ratings climbed steadily throughout the Eighties and Nineties, the song became inseparable from the program.

Outside of an ill-fated late-Seventies reunion, the Allman Brothers Band was unable to capitalize on the resurgence of interest in its music before finally reforming in 1989. There’s a bittersweetness, then, to the lighthearted sound of “Jessica” and its dedication to hope and life in the face of despair and death. The infant who inspired the song isn’t featured on Brothers and Sisters’ now-iconic front cover, however: that honor goes to Vaylor Trucks, the son of drummer Butch Trucks, captured in an autumn reverie on the grounds of The Farm. “I have an almost dreamlike memory of the way things were,” said Brittany Oakley, the daughter of Berry Oakley and his wife, Linda, who’s pictured on the LP’s back cover. “Parties, people giving the horses beer, various people in and out.” Though it may not have been evident back then, hindsight paints that golden landscape as a progressing sunset: the moment right before darkness falls.

Jessica (KORD-0070)

Related songs: