Edwin Starr will forever remain synonymous with “War,” his 1970 psychedelic soul milestone assailing America’s ongoing involvement in the decades-long conflict in Vietnam. But Starr was by no means a one-hit wonder. Eighteen months before declaring “War” on the pop charts, the singer hit paydirt with “Twenty-Five Miles,” one of the most propulsive singles ever released under the Motown Records aegis.

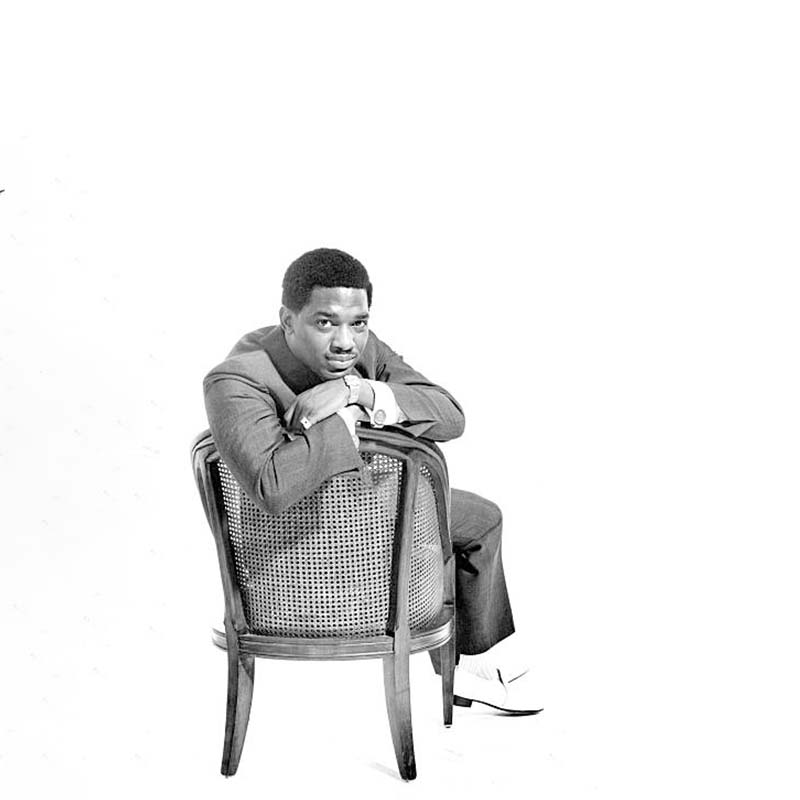

The stentorian-voiced Starr charted a singular path to Motown fame. He was born Charles Edwin Hatcher in Nashville in 1942 and raised in Cleveland, at age 13 forming a doo-wop group, the Future Tones, with younger brother Angelo and cousins Roger and Willie Hatcher. The Future Tones built a loyal local following playing school dances and other social functions, and in 1957 cut a single, “Roll On.” Starr was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1960, and after a hitch in Germany, he returned stateside to revive the Future Tones; when that effort proved unsuccessful, he signed on with Bill Doggett, the pianist whose 1956 King Records classic “Honky Tonk” sold more than four million copies and topped the Billboard R&B charts in excess of two months, also climbing to number two on the pop Hot 100. “It was less money than I was actually making,” Starr (a stage name suggested by Don Briggs, Doggett’s manager) told music historian Bill Dahl. “But it was a lot more experience. So I got a chance to get my road experience by traveling with Bill for two-and-a-half years.”

While performing with Doggett and His Combo in New York City, Starr spent his day off at the movies. “The movie happened to be Goldfinger — you know, the James Bond movie,” he told Dahl. “And that whole ideology behind the James Bond films happened to be the flavor of the month. I watched the movie like three times, and then went back to my hotel room, and I was sitting there contemplating on the idea of what the movie was all about, and trying to figure out how to incorporate that into a song. And I came up with ‘Agent Double-O-Soul.’” Starr presented the song to Doggett, but the pianist didn’t think Starr was ready to launch a solo career and advised him to wait a year. “I said to him ‘I can’t wait a year. This is a current topic now, and if I do wait, by the time I get a chance to actually go in and record it, it’ll be old hat.’” Starr and Doggett parted ways, and with the assistance of friend LeBaron Taylor, an on-air personality and program director at Detroit radio station WCHB, the singer dispatched “Agent Double-O-Soul” to Eddie Wingate, co-founder of Motown’s crosstown rival Ric-Tic Records.

Wingate is a fascinating figure in Detroit music lore. He was born and raised in Jim Crow Georgia, and sometime in the late 1930s he joined the legions of southern Blacks migrating north, driving his banged-up Model T to Detroit and landing a job on the Ford Motor Company assembly line. Wingate worked at Ford for close to a decade, building a substantial savings he earmarked to open his own restaurant. Then he discovered the numbers game, an illegal lottery where bettors attempt to pick three digits to match those that will be randomly drawn the following day. The numbers game was played in poor and working-class neighborhoods across the United States, and because it could be played for as little as a penny (for a typical payoff of 600 to 1), it was enormously popular: by 1928, several Detroit newspapers published the daily numbers results in their pages to stimulate sales. “[Wingate] had found out about ‘The Numbers’ from the hustlers that were all over the Black community,” writes Curtis Greene in a 2021 Journal essay headlined “Detroit’s First Black Godfather, Eddie Wingate Sr.” “Working at Ford gave Wingate the ability to win clients that played numbers because they could afford to… Eddie being the hungry and enterprising young man that he was, it was inevitable that he would meet the top mafiosos of Michigan. That sparked decades-long friendships that would end up making him richer than he’d ever imagined.”

A Federal Bureau of Investigation report dated July 1963 details Wingate’s rise based on information collected in the course of the agency’s investigation into Anthony Giacalone, a.k.a. Tony Jocks, a notorious figure in Detroit’s organized criminal underworld who vaulted to national attention in 1975 when he was named as one of two Mafia members scheduled to meet Jimmy Hoffa on the afternoon the Teamsters boss disappeared. According to an FBI informant close to Giacalone, the Detroit numbers business was “honest” until 1954, when Giacalone took over and installed a new system “whereby the winning number would be changed if it was one that would cause heavy payoffs.” At the time, “Eddie Wingate was a small man,” the FBI report reveals. “[The informant] stated Wingate came out of the South years before this and had been a cotton picker with no background and little education, but he was a shrewd man. When Wingate found out the number was being changed, he immediately paid unit heads and pickup men more money than anyone else, with the results that he took over more and more business. Today, he has more numbers business than anyone in Detroit.”

Wingate gradually expanded his growing empire into more legitimate businesses, acquiring residential and commercial properties across Detroit, most notable among them the 20 Grand Hotel, from where he ran his numbers racket. (“During the Detroit riots of 1967, Ed placed two of his employees with pump shotguns on the roof of his motel,” recalled Detroit guitarist extraordinaire Dennis Coffey. “No one came near it until the riot was over.”) Wingate also served as the silent majority owner of the hotel’s next-door neighbor, the 20 Grand Supper Club, owned on paper and for public relations purposes by white businessmen Bill Kabbush and Marty Eisner, but established to serve a Black clientele. The 20 Grand Supper Club opened in 1953, and when fire destroyed the site five years later, it was rebuilt as a multiplex facility for Black audiences, complete with a ground-floor bowling alley, the Gold Room (a banquet and cabaret hall with seating for up to 1,200 people) and the Driftwood Lounge, which hosted virtually all of the major Black entertainers of the period, sometimes for multi-week residencies. Somewhere along the way, Wingate befriended Berry Gordy Jr., the entrepreneurial-minded songwriter and producer who launched Motown Records in early 1959; Gordy later used the Driftwood Lounge as a launching pad for future Motown superstars including the Miracles, the Temptations, the Supremes and Little Stevie Wonder, allowing them to hone their onstage presence in front of a hometown crowd before hitting the road to tour the so-called “chitlin’ circuit” of Black-owned nightclubs.

Gordy eventually approached Wingate about investing in Motown, but Wingate had other plans. He and lover Joanne Jackson Bratton (then the wife of Johnny “Honey Boy” Bratton, a professional boxer who in 1953 briefly held the World Boxing Association welterweight title vacated by the legendary Sugar Ray Robinson) launched Golden World Records and its Myto Publishing arm in late 1961, taking the unusual step of advertising for talent via local newspapers — a cattle call that yielded producer, arranger and pianist George “Teacho” Wilshire and singer Sue Perrin, whose debut single “I Wonder” inaugurated the Golden World catalog in early 1962. Wingate and Bratton spun off Ric-Tic Records (so named for Bratton’s deceased son Derek) later in 1962, and around the same time, they began making plans to build their own state-of-the-art recording studio on the site of a former electrical goods store at 3246 West Davison Ave., less than four miles northwest of Motown’s fabled Hitsville USA facilities. Wingate and Bratton recruited chief recording engineer Bob d’Orleans to oversee construction and contracted Ken Hamman, at that time the president and chief engineer at Cleveland Recording, to build a custom recording console.

Golden World notched its first Billboard Top Ten single in the spring of 1964 with the release of “(Just Like) Romeo and Juliet,” an upbeat dancer from blue-eyed soul group the Reflections, whom Wingate poached from Detroit’s Kay-Ko label after the success of their regional hit “You Said Goodbye.” Golden World Studio opened for business roughly a year later, and its impact on the Detroit music business was seismic. According to Nelson George’s milestone Motown history Where Did Our Love Go?, Gordy paid session musicians just $7.50 per side as of 1962: “The players got their money in cash; the only record of the sessions was a receipt a secretary might make up and sign,” George writes. “The local musicians’ union didn’t pressure Motown to pay union scale until 1965, though its pay scale was common knowledge among Detroit’s Black musicians.” Wingate exploited Gordy’s frugality, luring members of Motown’s celebrated Funk Brothers session crew to Golden World by promising them union scale wages, and while any musicians under contract with Motown caught moonlighting by Gordy were fined $1,000 for their malfeasance, Wingate was so pleased with their efforts that he usually paid the fines himself.

All of which explains how it came to be that Funk Brothers mainstays including keyboardist Earl Van Dyke, bassist Bob Babbitt and drummer Benny Benjamin backed Starr on the brassy “Agent Double-O-Soul,” recorded at Golden World under the auspices of producer Richard Parker and released in the summer of 1965, six months ahead of Thunderball, the James Bond film series’ most commercially successful entry to date. “Agent Double-O-Soul” reached number eight on the Billboard R&B charts and peaked at number 21 on the Hot 100, and both Dennis Coffey and bassist James Jamerson slipped out of Motown’s clutches long enough to play on Starr’s follow-up effort, the hard-driving Motown soundalike/future Northern soul perennial “Stop Her on Sight (S.O.S.),” which the singer co-wrote with co-producers Richard Morris and Al Kent. “The initial thought of the song was, ‘S.O.S. — Sending Out Soul,’” Starr told Bill Dahl. “Richard and I changed it to ‘Stop Her on Sight’ to make it like a girl/guy song. But the whole idea of the song came from the television program 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. ‘Cause I was laying watching that, and they did the Morse code thing on the TV show. And that’s where I got the idea for the record.” Ric-Tic released “Stop Her on Sight (S.O.S.)” in January 1966, scoring another Billboard R&B Top Ten hit.

Berry Gordy Jr. had seen more than enough. “Motown went straight for the throat,” George writes in Where Did Our Love Go? “For independent labels, nothing could be more important than a good relationship with distributors across the country, and at some point Motown allegedly made it hard for local competitors to receive payment from them.” But Golden World continued to thrive, and in September 1966 Gordy acquired Golden World Studio and Myto Publishing in September 1966 for a reputed $1 million; moving forward, Golden World would be known as Motown Studio B, while the original Hitsville facility remained Motown Studio A. Gordy later went on to purchase Golden World Records and its affiliates, including Ric-Tic, and in the process acquired Starr’s contract — much to the singer’s surprise.

“I didn’t know it at all,” Starr told Dahl. “It was a done deal by the time I got back to the United States. I was in England performing at that time, and I went back to go to the Apollo Theatre to co-star with the Temptations. One of the Temptations told me that I was a Motown artist. It was a shock to the system, to say the least.” Wingate, on the other hand, exited the music business after finalizing the Motown deal. In early 1977, he was one of five men arrested by the FBI for masterminding Detroit’s citywide bookmaking and numbers-running operation, and while all five pleaded nolo contendere and paid heavy fines, they were never convicted. After a federal grand jury brought indictments against Anthony Giacalone and his mafioso brother Vito, Wingate sold his business interests and left Detroit for good; he settled in Florida, and died in Las Vegas in 2006.

Starr’s Motown career got off to an inauspicious start: his first single for his new label, “I Want My Baby Back,” was written by Motown staff producer Norman Whitfield in tandem with the Temptations’ Eddie Kendricks and the vocal group’s guitarist Cornelius Grant, but ran out of gas at number 120 on the Billboard pop chart. His second release, 1968’s “I Am the Man for You Baby,” fared only marginally better, reaching number 112 but clawing to number 45 on the Billboard R&B countdown. Starr wrote his third Motown single, “Twenty-Five Miles,” several years earlier to close out his performances at Mickey’s Hideaway, a college bar in East Lansing, Mich. Motown initially rejected the song, labeling it “too rock’n’roll,” but when Starr performed “Twenty-Five Miles” on Detroit television’s 20 Grand Live, overwhelming viewer reaction caused label brass to reconsider their decision. Producers Johnny Bristol and Harvey Fuqua added the unforgettable line “Come on feet, feet don’t fail me now” to Starr’s portrait of a man on the march to reunite with the woman he loves; Bristol and Fuqua also contributed “Twenty-Five Miles’” distinctive foot-stomping rhythm, recorded in conjunction with members of another floundering Motown act, the Spinners.

While “War” remains Starr’s crowning commercial achievement, “Twenty-Five Miles” is arguably the stronger record. It doesn’t sound anything at all like a typical Motown hit: Bristol and Fuqua drew inspiration from the obscure “32 Miles Out of Waycross (a.k.a. Mojo Mama),” authored by Bert Berns and Jerry Wexler and recorded at Alabama’s Muscle Shoals Sound Studio in 1967 by the great southern soul shouter Wilson Pickett. (The producers drew so much inspiration from “32 Miles Out of Waycross” that Berns and Wexler were ultimately awarded co-writer credits.) The Funk Brothers’ approximate the gritty, dynamic Muscle Shoals Sound with the same energy and aplomb that define the Motown Sound: apart from Benny Benjamin, whose muscular drums mirror the fatigued footsteps and steely determination of Starr’s unstoppable protagonist, it’s all but impossible to identify which Funk Brothers are playing on “Twenty-Five Miles” (blame those Motown bookkeeping issues cited earlier), but Starr’s fire-and-brimstone vocals are unmistakable even from miles away. When it comes to sheer raw power, he may be the most impressive singer ever to headline a Motown release.

Scholar Eric v.d. Luft argues “Twenty-Five Miles” clandestinely anticipates the social and moral outrage Starr would unleash in full several months later when he recorded “War,” which led him back to “I Want My Baby Back” producer Norman Whitfield. “‘Twenty-Five Miles,’ which at first seemed to be just a love song, implied a criticism of the low status that whites still imposed on Black people in society,” Luft notes in 2009’s Die at the Right Time! A Subjective Cultural History of the American Sixties. “The idea was that the singer was so devoted to his sweetie that he would gladly walk 25 miles to see her, no matter how tired he got or how much his feet hurt. He had to walk. There was no other way to reach her. Yet (we thought), poor whites who were separated from their sweeties would not have had to walk long distances to see them. They could have hitchhiked. We saw lots of hitchhikers in the Sixties — but how many Black hitchhikers? That mode of travel was not safe for them, and they knew it. Moreover, Starr’s image of an optimistic young Black man walking down the road reminded us of their ordeal expressed in civil rights marches.”

“Twenty-Five Miles” soared to the number six position on both the pop charts and the R&B charts in early 1969, reviving Starr’s flagging career. However, the title of its follow-up, “I’m Still a Struggling Man,” proved bitterly appropriate when the single stalled at number 27 R&B and number 80 pop, and by early 1970, Starr’s days at Motown again appeared numbered. He was not the first choice to record “War” — Whitfield and co-writer Barrett Strong originally penned the pacifist anthem for the Temptations, but Berry Gordy flatly resisted calls from college students and activists to release the group’s LP version as a single, fearing it might jeopardize their image or alienate more conservative audiences. Motown would consent to releasing “War” to radio and retail, however, provided Whitfield re-recorded the song with another artist — one less vital to the label’s bottom line. Starr raised his hand, cutting the single at Hitsville USA on May 15, 1970, 11 days after members of the U.S. National Guard opened fire on anti-war protesters at northeast Ohio’s Kent State University, killing four students and wounding nine others. “War” topped the Billboard pop chart in August 1970, and went on to win the Grammy Award for Best Male R&B Vocal Performance.

Starr left Motown after completing work on the soundtrack to the 1973 Blaxploitation film Hell Up in Harlem but continued recording and touring the U.S. and Europe, scoring a pair of disco-inspired U.K. hits in 1979 with “Contact” and “Happy Radio.” He moved to Britain in 1983, and in the decades to follow became a fixture on the Northern soul revival circuit. Starr suffered a fatal heart attack at his Nottinghamshire home on Apr. 2, 2003; he was 61. “It’s not always about success,” Starr said, looking back on his career in an undated interview with Portsmouth-based broadcaster MyTV. “It’s about being able to do what you do, and enjoy it.”

Related Songs