When the Temptations released their debut Motown Records single “Oh Mother of Mine,” Paul Williams was firmly ensconced as the group’s lead singer. But by the time the Tempts topped the charts with “I Can’t Get Next to You,” Williams’ life and career were in irreversible decline, his formidable baritone confined almost exclusively to backing vocals and the occasional B-side showcase.

The arc of Williams’ triumph-to-tragedy narrative begins in Birmingham, Ala.’s Ensley neighborhood. The son of Rufus Williams, a member of gospel’s Ensley Jubilee Singers, he and lifelong best friend Eddie Kendricks grew up singing in their church choir, and In 1955, they teamed with fellow choir members Kell Osborne and Willie Waller to form a doo-wop quartet, the Cavaliers. Two years later, the Cavaliers moved north to Cleveland and signed with manager Milton Jenkins, who convinced them to relocate to Detroit, where they adopted a new name, the Primes, and in 1959 spun off a sister act, the Primettes, later renamed the Supremes. The Primes dissolved in 1960, but when Otis Williams (no relation), Melvin Franklin and Elbridge “Al” Bryant of Detroit’s Distants formed a new vocal group, the Elgins, they recruited Williams and Kendricks to complete the lineup. The Elgins auditioned for Motown founder Berry Gordy Jr. in March 1961, and on the same day they signed Gordy’s contract offer, they changed their name one last time to become the Temptations, a moniker suggested by Billie Jean Brown, the onetime Motown tape librarian who later headed the label’s demanding quality control department.

Gordy assigned Motown staff producer William “Mickey” Stevenson and future R&B cult icon/rap godfather Andre Williams (also no relation) to helm the vibrant “Oh Mother of Mine,” released in July 1961 on Motown’s short-lived Miracle imprint. Miracle (slogan: “If it’s a hit, it’s a Miracle”) was deactivated and reorganized as Gordy Records in the wake of the Temptations’ follow-up, the Berry Gordy-produced “Check Yourself,” which first features tenor Otis Williams, then a spoken interlude from bass singer Melvin Franklin, before Paul Williams takes over the rest of the way. Neither record was a hit, and Gordy spotlighted Eddie Kendricks’ silken, soaring tenor on the Temptations’ third single, 1962’s “(You’re My) Dream Come True,” which climbed to number 22 on Billboard’s R&B singles chart — high enough to land the quintet a spot on the Motortown Revue package concert tour, and sealing Williams’ fate as a supporting player within the group. Kendricks also performed lead on the Tempts’ Smokey Robinson-produced breakthrough hit “The Way You Do the Things You Do,” which in early 1964 reached number 11 on the Billboard Hot 100, while newest member David Ruffin (hired after Al Bryant was fired) took lead for the first time on “My Girl,” which in early 1965 became the Temptations’ first number one pop single.

Either Ruffin or Kendricks featured on subsequent Temptations perennials like “Get Ready,” “Ain’t Too Proud to Beg” and “(I Know) I’m Losing You,” further relegating Williams to the background, even on album tracks and B-sides. He nonetheless remained central to the group’s stage act as its premier dancer and de facto choreographer: Gerald Posner’s book Motown: Music, Money, Sex and Power notes that when the Temptations performed a nine-day run at the Brooklyn Fox Theater alongside Motown labelmate Marvin Gaye and British soul queen Dusty Springfield, the group “sent the crowd wild” in bright purple suits offset with flowing white shirts, large white buttons and white patent-leather shoes. “It was about style and elegance, but also suggested romance and, frankly, sex, something Paul deliberately made part of our image,” Otis Williams told Posner. But Williams craved a return to the spotlight, and after reminding his colleagues “Shit, I can sing too!” he was assigned lead vocals on the 1965 single “Don’t Look Back.” Radio deejays across the country ignored the track in favor of its Ruffin-led flipside “My Baby,” however, ensuring Williams was not the featured lead on a Temptations A-side again. “Don’t Look Back” nevertheless became his signature song, regularly closing out Temptations live performances: Williams even seized on the “Don’t Look Back” lyric “Keep on walkin’” to develop a crowd-pleasing strut across the stage. (Listen closely to the 1967 LP Temptations Live! to hear the women in the audience lustily calling for the song to be performed.)

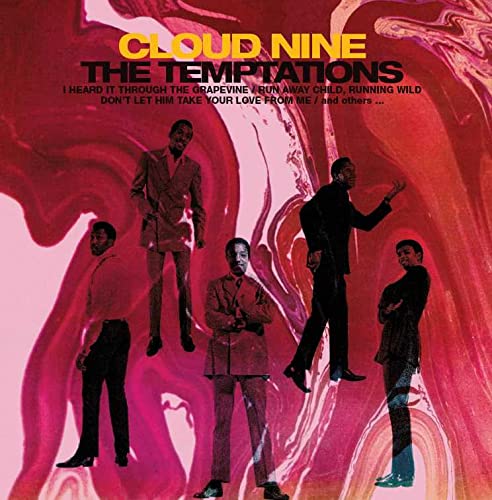

“I Can’t Get Next to You,” the second single from the Temptations’ 1969 LP Puzzle People, was produced by Norman Whitfield, who co-wrote the song with Barrett Strong. Whitfield first teamed with the Tempts on 1964’s ”Girl (Why You Wanna Make Me Blue),” but he assumed full control of their creative destiny following the October 1968 release of the Grammy-winning “Cloud Nine,” ground zero for the psychedelic soul aesthetic the producer would continue to explore and expand over the duration of his partnership with the group. “Cloud Nine” — inspired directly by the trailblazing flower-power funk of Sly and the Family Stone’s Top Ten pop hit “Dance to the Music” — presents an unflinching portrayal of inner-city life, a “dog-eat-dog world” where “it ain’t even safe no more to walk the streets at night.” The song’s impoverished protagonist seeks escape in drugs that transport him “a million miles from reality” — an innerspace odyssey navigated by the lysergic wah-wah guitar of Dennis Coffey (a new addition to Motown’s fabled studio crew, the Funk Brothers) and the incendiary conga drums of guest percussionist Mongo Santamaria.

“Cloud Nine” features all five Temptations trading lead vocals round-robin style — a move Whitfield borrowed directly from the Sly Stone playbook, and which he repeated for the ferocious “I Can’t Get Next to You,” which begins with a burst of applause cut short by the song’s lead vocalist, newest Temptation Dennis Edwards, who joined the lineup in June 1968 to replace the cocaine-addicted David Ruffin. “Hold it everybody,” Edwards commands. “Hold it, hold it. Listen.” From there, a snatch of Earl Van Dyke’s barrelhouse-bluesy 1877 Steinway Grand gives way to an eruption of Muscle Shoals-inspired horns — a head-spinning sequence of seemingly disconnected fragments that magically cohere into the flat-out funkiest Motown single to date. “I Can’t Get Next to You” spent two weeks atop the Billboard Hot 100 in October 1969, usurping the Archies’ bubblegum blockbuster “Sugar, Sugar,” as well as reigning five weeks at number one on Billboard’s Top R&B Singles countdown.

The flipside of “I Can’t Get Next to You,” the charming but slight ballad “Running Away (Ain’t Gonna Help You),” features Williams on lead vocal — his final featured performance as a member of the group he co-founded eight years earlier. By the time the single dropped on July 30, 1969, Williams’ personal life was in shambles. For years he suffered from sickle-cell disease, a condition exacerbated by the pressures of performing and touring; Celebrity House West, the fashion boutique he opened in downtown Detroit, was also in dire straits, and he owed the government more than $80,000 in back taxes (comparable to roughly $650,000 as of mid-2023). Williams was further consumed by an affair with Winnie Brown, the Supremes’ hair stylist, but remained devoted to his wife and children. Moreover, after Berry Gordy recruited vaudeville veteran Cholly “Pops” Atkins to choreograph dance routines for the Motown’s biggest acts, Williams wielded increasingly minimal influence over the Tempts’ stage show, and after years of admonishing the other members of the group to steer clear of alcohol, he turned to the bottle to ease his physical and emotional anguish. “Paul was drinking milk. And he would say, `Now, you guys should stop drinking that [alcohol]. Drink milk. Stay healthy,’” Otis Williams recalled in a 1998 interview with Deseret News. “So to see a guy come from drinking milk to drinking, sometimes, two to three fifths of Courvoisier a day — that was kind of hard to take.”

Williams’ descent was far from the only internal challenge facing the Temptations. The massive success of records like “Cloud Nine” and “I Can’t Get Next to You” granted Norman Whitfield even greater control over the group’s direction, and he and Barrett Strong continued pushing their music further into the unknown, authoring a series of street-smart, socially conscious and vividly cinematic records informed by acid rock and funk. This development did not sit well with Eddie Kendricks, who called Whitfield’s most grandiose studio experiments “freaky.” Kendricks also remained resentful of David Ruffin’s dismissal from the Temptations, and maintained Motown was cheating the group out of significant sums of money. After Williams criticized Kendricks for missing a dance step, the two boyhood friends got into a heated, expletive-laden argument that culminated in Kendricks pulling a knife and slamming Williams against a wall. For the most part, however, the Temptations rallied around Williams, recruiting Richard Street, then a member of Motown’s Monitors as well as the former lead vocalist of the Distants, to sing most of Williams’ parts from backstage behind a curtain; on nights when Williams was unable to perform at all, Street took his place onstage.

Williams finally consented to seek medical treatment in the spring of 1971, and when doctors discovered a spot on his liver, they advised him to retire from performing: Street was named his permanent replacement, although the Temptations kept Williams on the payroll as an advisor and choreographer for the next two years, and he continued to earn his one-fifth share of the group’s royalties. Williams mounted a solo career in early 1973, with Kendricks — now a solo artist as well — producing and co-writing his friend’s debut single, “Feel Like Givin’ Up.” Motown declined to release the record, however, and on Aug. 17, 1973, the 34-year-old Williams was found dead inside a car parked a few blocks away from Motown’s Hitsville USA recording studio. A gun was found next to his body, and his death was ruled a suicide. More than 2,500 mourners, including fans, fellow artists and even politicians, attended Williams’ funeral, where David Ruffin sang one of his late colleague’s favorite songs, “The Impossible Dream,” before collapsing in grief.

“[Williams] had the pipes to rival just about any male vocalist of the time,” writes producer Paul Nixon in his liner notes to the 2010 archival release A Cellarful of Motown! Volume 4, which includes the previously unreleased Williams solo cut “I Need You Now More Than Ever,” recorded less than two weeks before the singer’s death. “He remains one of the Temptations’ finest.”

Related Songs