“Free Bird” is the sacred text of Southern rock, and like all sacred texts, it is the object of both devotion and derision. Lynyrd Skynyrd’s elegiac magnum opus is so deeply burned into the collective musical consciousness, so inescapable across decades of nonstop radio airplay, that it’s all but impossible to separate the song from the passions it inspires. Because everyone knows “Free Bird,” everyone has an opinion about “Free Bird” — which is its blessing and its curse. You either love it or hate it; indifference is not an option.

“Free Bird,” released in 1973 as the closing track to Lynyrd Skynyrd’s debut LP (Pronounced ‘Lĕh-‘nérd ‘Skin-‘nérd), was written by guitarist Allen Collins and vocalist Ronnie Van Zant, and if you don’t like the song, it might amuse you to learn Van Zant didn’t like it much at first, either. “Allen had these chords, and he’d play them over and over, but at first Ronnie thought there were too many chord changes to write lyrics to,” Skynyrd guitarist Gary Rossington told Garden & Gun. (These chords were eventually recorded using Rossington’s 1959 Gibson Les Paul Sunburst guitar, known as “Bernice.”)

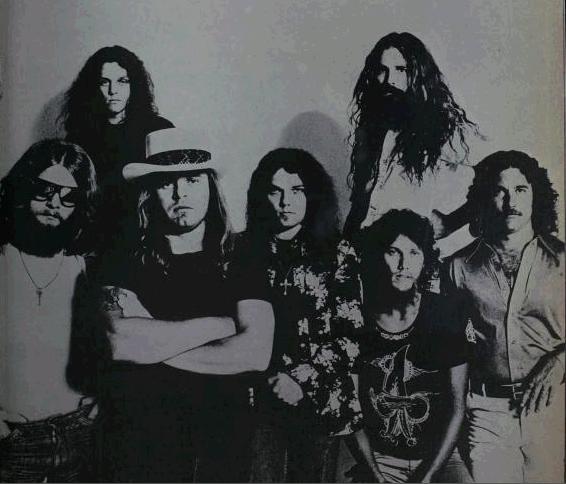

Van Zant, Collins and Rossington formed the first incarnation of Lynyrd Skynyrd in Jacksonville, Fla. in 1964, cycling through a series of names including My Backyard, the Noble Five and the One Percent before adopting their familiar moniker in mocking tribute to Leonard Skinner, a PE teacher notorious for enforcing their high school’s policy against long hair on boys. By 1970 Lynyrd Skynyrd was a mainstay of the Jacksonville music scene, headlining local venues and opening for national touring acts; their outlaw blues-rock encompassed elements of country music, R&B and even gospel, coalescing into a rugged, swaggering sound as distinctly Southern as sweet potato pie.

The material cut for (Pronounced ‘Lĕh-‘nérd ‘Skin-‘nérd) was workshopped by the group in its rural Jacksonville rehearsal space (a suffocatingly hot tin-roofed shack nicknamed the Hell House) and further honed onstage. Producer Al Kooper, who signed Lynyrd Skynyrd to his Sounds of the South label, later noted that by the time the band entered Doraville, Ga.’s Studio One to record the album, every note was essentially etched in stone, with a policy against improvisation strictly observed. But while the (Pronounced ‘Lĕh-‘nérd ‘Skin-‘nérd) version of “Free Bird” unfurls across a span of more than nine minutes, the song was originally much simpler and much shorter: a demo recorded in October 1970 and included on a 1991 retrospective box set runs just over four minutes.

According to Rossington, the blistering, double-tracked guitar solo performed by Collins on his trademark 1958 Gibson Explorer and immortalized on the (Pronounced ‘Lĕh-‘nérd ‘Skin-‘nérd) iteration of “Free Bird” evolved over time — and out of necessity. “We started playing it, just the slow part, at clubs,” Rossington recalled. “Then, after a few sets, Ronnie would say, ‘Y’all play a little longer, my throat’s hurting and I need a break.’ We’d play a minute longer one night, then the next night two minutes or three, and then we’d jam out for five minutes or more. One guy at this club in Atlanta said ‘Would y’all play that song that has a big ending? That one we can all dance to at the end?'” From there, “Free Bird” expanded yet again, this time to incorporate Skynyrd roadie Billy Powell’s luminously melancholy piano introduction — an addition that so impressed the rest of the group that Powell was asked to officially join the lineup as a full-time keyboardist.

(Pronounced ‘Lĕh-‘nérd ‘Skin-‘nérd) reached stores on Aug. 13, 1973; Sounds of the South’s parent label MCA Records initially resisted releasing “Free Bird” as a single, opting for the more conventional “Gimme Three Steps.” “They thought [‘Free Bird’] was too long to be a hit,” Rossington told Louder. “Mind you, so did we.” But as Skynyrd attracted a wider audience and “Free Bird” soared in popularity with concertgoers, MCA finally relented, shipping a 4:41 single edit to radio and retail in November 1974. This version, which lopped off all but about a minute of Collins’ guitar solo, reached the Billboard Top 40 in early 1975, climbing to a peak of No. 19 on Jan. 25. A live version culled from the One from the Road concert album reentered the charts in late 1976, topping out at No. 38 in January 1977 — nine months before Lynyrd Skynyrd’s chartered Convair CV-240 crashed into a heavily forested swampland outside of Gillsburg, Miss., claiming the lives of Van Zant and five others onboard.

There is no disentangling the legacy of “Free Bird” from this crash, one of the great tragedies in music history. “Free Bird” was the last song the classic lineup of Lynyrd Skynyrd played during its final concert in Greenville, S.C. on Oct. 20, 1977, and Van Zant’s lyrics — “If I leave here tomorrow/Would you still remember me?/For I must be traveling on now/’Cause there’s too many places I’ve got to see” — now seem eerily prescient. Moreover, during Lynyrd Skynyrd’s 1975 appearance on the BBC’s The Old Grey Whistle Test, Van Zant dedicated the song to the Allman Brothers Band’s Duane Allman and Berry Oakley, who died in motorcycle accidents roughly one year apart, declaring “They’re both free birds.” In fact, “Free Bird” is so synonymous with death that it is regularly played at funerals and memorials across the U.S. — a reassuring reminder the deceased is “as free as a bird now.”

But “Free Bird” is much more than a chronicle of death foretold. For starters, it is the definitive Southern rock song — a subjective statement, admittedly, but it ranks number one in C. Eric Banister’s 2016 book Counting Down Southern Rock: The 100 Best Songs (ahead of the Marshall Tucker Band’s “Can’t You See,” the Allman Brothers Band’s “Ramblin’ Man” and Skynyrd’s own “Sweet Home Alabama“), and countless other websites and fan resources place it atop their lists as well. It is unmistakably Southern music, to be sure: from Al Kooper’s churchyard organ to Rossington’s plaintive slide guitar to Van Zant’s poignantly world-weary vocal, “Free Bird” unfolds as slowly and as deliberately as a summertime Sunday — at least until Collins’ solo turns the music inside-out.

“Free Bird” is also a distinctly American song, albeit in ways that are complex and problematic. Whatever “Free Bird” means in the wake of Van Zant’s death, during his lifetime it was first and foremost a paean to wanderlust and independence: “It’s about what it means to be free, in that a bird can fly wherever he wants to go,” Van Zant once said. “Everyone wants to be free. That’s what this country’s all about.” But this reading is far too facile, especially given Skynyrd’s complicated relationship with the Southern culture that shaped and embraced its music.

“From the outset, Skynyrd danced on the edge of controversy, performing in front of the Confederate flag and alluding to George Wallace, the segregationist governor of Alabama, in song,” Stephen Thomas Erlewine wrote for Rolling Stone in 2018. “These incidents were later explained away by the band: [Kooper] pushed the group to adopt the Stars and Bars, assuming it’d accentuate their Southerness and rebellion, while the ‘Sweet Home Alabama’ lyric ‘In Birmingham they love the governor’ was said to be undercut by the backing vocals chanting ‘boo boo boo’ afterward. Such after-the-fact justifications paint Lynyrd Skynyrd in the best possible light, suggesting that any ugliness was not the fault of the band: either they had good intentions or were just playing the industry’s game.”

In the case of “Free Bird,” Van Zant is right: everyone does want to be free. But speaking to the Chicago Tribune in 2009, former Skynyrd drummer Artimus Pyle admitted that in the years immediately following Van Zant’s death, “Free Bird” became “this defiant thing” — what Tribune writer Christopher Borrelli called “a sassy thumb in the eye of encroaching cosmopolitanism.” In other, blunter words, it’s a redneck anthem, beloved by many working-class whites who would deny the same basic freedoms celebrated by “Free Bird” to those who look, think and feel differently than they do. Lynyrd Skynyrd, which reunited in 1987 (with Van Zant’s younger brother Johnny assuming frontman duties), openly courted Southern conservative audiences in the later years of its career: in a 2004 New York Times article headlined “GOP’s Southern Strategy? Cranking Up Lynyrd Skynyrd,” which noted the large number of Southern rockers performing at that year’s Republican National Convention, Skynyrd’s manager Ross Schilling proclaimed ”They make no qualms about it: they are definitely a Republican band,” adding that Skynyrd performed at a party during the Republican National Convention in 2000 and at several campaign stops for then-President George W. Bush.

Patterson Hood, leader of latter-day Southern rock band Drive-By Truckers — whose two-LP masterpiece Southern Rock Opera grapples with Skynyrd’s music and mythos — told the Chicago Tribune that in the small Alabama town where he came of age, “Free Bird” was “deadly serious, and still is. But I feel like I could write you a dissertation in defense of it as being one of the most underrated songs in rock history and I could write about its utter banality, and in both papers I would be sincere. To be truthful, it didn’t even occur to me there might be irony in ‘Free Bird’ until I moved from my small town to a city.”

And, of course, “Free Bird” is also a punchline. To its critics, and there are many, the song is overplayed and overripe, a Dixie-fried “Stairway to Heaven” whose omnipresence on classic rock radio — a broadcast format perennially dominated by music made by and for white men — serves as a bitter reminder of how fossilized and how myopic rock fandom has grown. Not to mention that for many years, screaming for “Free Bird” at live performances headlined by acts other than Lynyrd Skynyrd was a common occurrence “guaranteed to elicit laughs from drunks and scorn from music fans who have long since tired of the joke,” notes a 2005 Wall Street Journal article about the phenomenon. (The trend has since abated; no less than Bob Dylan may have delivered the fatal blow when in 2016, he and his band actually accommodated the request, closing a Berkeley, Calif. performance with a “Free Bird” for the ages.)

“Free Bird” endures regardless. It is enshrined in the Grammy Hall of Fame and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s 500 Songs That Shaped Rock and Roll, and in 2008, it also landed at number eight on Guitar World‘s countdown of the 100 Greatest Guitar Solos.

“Ronnie and Allen didn’t live long enough to see it turn into a classic,” Rossington told Garden & Gun. “They didn’t get to see that everybody everywhere knows ‘Free Bird.’ It’s played at graduations, weddings and funerals, and a lot of people say we got them through college with ‘Free Bird.’ Every night, we look out at the audience and you see people singing every lyric with Johnny. At the end, everybody starts jumping up and down, and it’s emotional to watch the audience do that. The song lets you think about your love or people you’ve lost.”

Related Songs