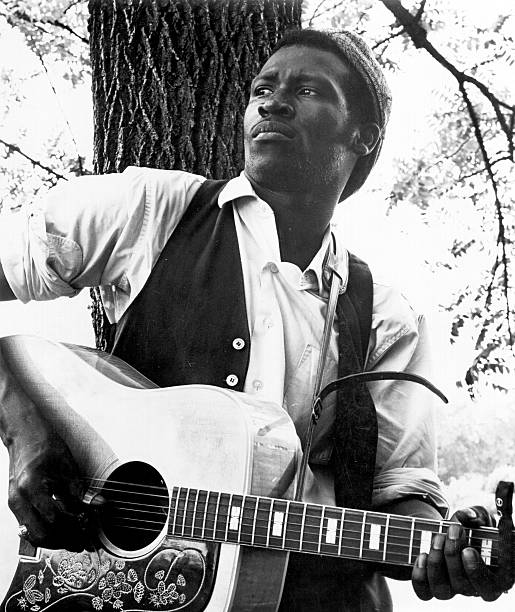

The Allmans recorded At Fillmore East in March 1971, a little less than a dozen years after the death of Blind Willie McTell, the author of “Statesboro Blues” (so named for Statesboro, Ga., which he considered his hometown). McTell — a singer and 12-string guitarist who occasionally swapped his graceful, syncopated fingerstyle technique in favor of slide guitar, a rarity among ragtime bluesmen — first cut the song in October 1928, one of eight sides he recorded for the Victor label. Its first-person, nonlinear narrative recounts the tale of a desperate man pleading with a woman to let him in her house, warning “When I leave this time, pretty mama, I’m going away to stay.” The mysterious malady addressed in the title seems to afflict McTell’s entire family: “I woke up this morning/Had them Statesboro blues/I looked over in the corner/Grandma and grandpa had ’em too,” he sings (although subsequent renditions of the song feature shorter, more streamlined lyrics).

“Statesboro Blues” entered the counterculture consciousness in 1968, when next-generation bluesman Taj Mahal included a modernized version on his self-titled debut album. That same year, Mahal’s rendition also surfaced on the best-selling The Rock Machine Turns You On, a CBS Records compilation considered the first bargain-priced sampler album. Mahal’s “Statesboro Blues” directly inspired the Allman Brothers Band to eventually add the song to its own repertoire: According to the ABB’s singer and keyboardist Gregg Allman, he gifted his older brother the Taj Mahal record for his 22nd birthday alongside a small glass bottle of decongestant pills, and Duane — who’d never previously attempted slide guitar — promptly emptied the pills, washed the label off the bottle, and mastered the song by day’s end.

Pete Carr, a guitarist in the Hour Glass (a pre-Allman Brothers Band act featuring both siblings), remembers it a bit differently. “We went to see Taj Mahal, and he had Jesse Ed Davis with him. They did ‘Statesboro Blues,’ and Davis played slide on it. After hearing that, Duane started practicing slide all the time,” Carr told Randy Poe, author of the 2006 biography Skydog: The Duane Allman Story. Fellow Hour Glass alum Paul Hornsby added “[‘Statesboro Blues’] was the first song that Duane played slide on in the Hour Glass. Of course, now when you think of ‘Statesboro Blues,’ you think of the Allman Brothers’ version, [but] we pretty much did the same arrangement as Taj.”

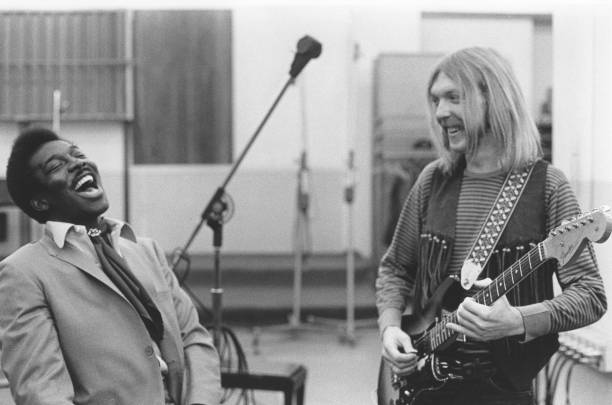

Both Duane and Gregg Allman learned to play music by copying their favorite records. While Gregg was the first of the brothers to pick up the guitar, purchasing a Silvertone model from a Sears store near the family’s Daytona Beach, Fla. home, Duane quickly leapfrogged him, and Gregg eventually migrated to keyboard. The Allmans played in a series of bands throughout their teen years, covering a wide range of Top 40 and R&B hits (many of the latter first discovered via Nashville R&B station WLAC). After the Hour Glass split following a pair of little-noticed LPs for Liberty Records, Gregg pursued a solo career, and Duane decamped to Muscle Shoals, Ala., working as a session guitarist at the renowned FAME Studios and turning heads with contributions to recordings from Wilson Pickett, Aretha Franklin and King Curtis, among others.

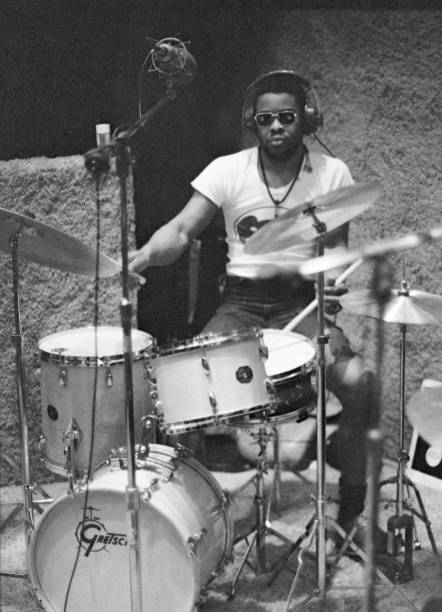

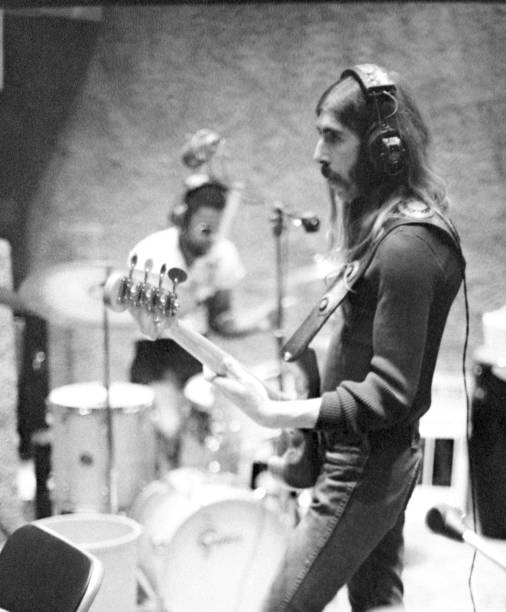

While at FAME, Duane began laying the foundations for what would become the Allman Brothers Band, which he envisioned to feature two lead guitarists and two drummers. After recruiting guitarist Dickey Betts, bassist Berry Oakley and drummers Butch Trucks and Jai Johanny “Jaimoe” Johanson, Duane called upon Gregg to return from Los Angeles (where he remained after the Hour Glass dissolved) and join the group at its Jacksonville, Fla. practice space. Four days after Gregg’s arrival, on March 30, 1969, the newly-minted Allman Brothers Band played its first live date at the Jacksonville Armory, unveiling a scorching, improvisatory fusion of blues, country, jazz and rock that spread like kudzu to inspire the southern rock of contemporaries including Lynyrd Skynyrd, Molly Hatchet and the Marshall Tucker Band, as well as latter-day descendants like Phish and Widespread Panic, who borrowed liberally from the Allmans’ genre-bending ethos and taut, richly complex instrumental exchanges to pioneer the so-called ‘jam band” circuit that flourished during the 1990s and beyond.

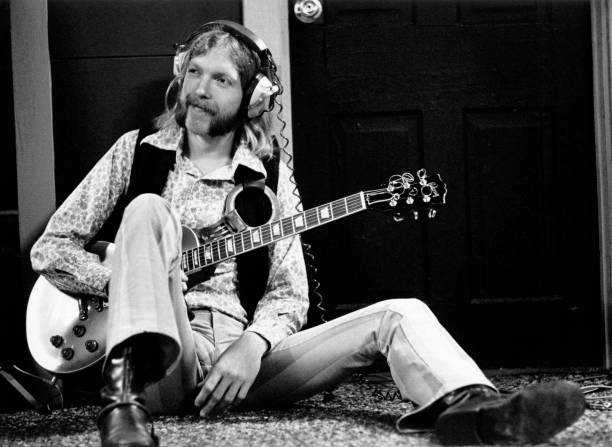

The Allman Brothers Band’s first two LPs for Phil Walden’s Capricorn Records, a self-titled 1969 effort and 1970’s Idlewild South, failed to attract much attention at retail, but the group built a nationwide grassroots following by touring relentlessly, playing more than 300 dates in 1970 alone. That same year, Duane Allman contributed lead and slide guitar to Eric Clapton’s landmark Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs, credited to Derek and the Dominos: Allman and Clapton’s twisting, twinning guitar duels evoked Allman’s six-string showdowns with Betts, each pushing the other to new peaks of creativity and intensity, and it can be argued that Clapton never scaled the same heights again. He ultimately asked Allman to join Derek and the Dominos on a full-time basis, and the offer was briefly considered but declined.

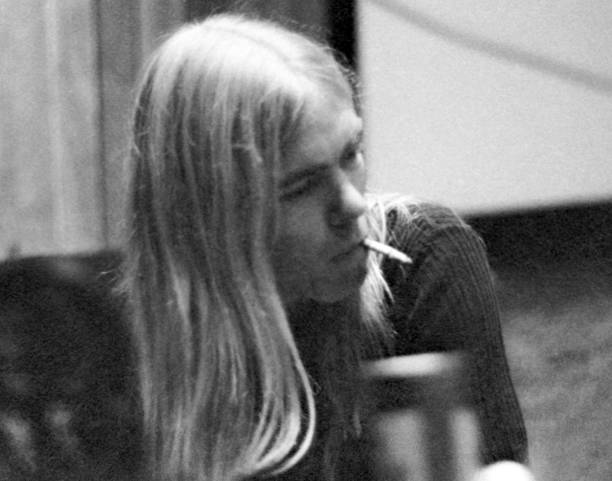

By 1971, the Allmans’ fortunes began to change as their protean live performances reached mythic status among concertgoers and promoters alike, and their average earnings doubled. “We realized that we got a better sound live and that we were a live band,” Gregg Allman explained in Alan Paul’s One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band. “We were not intentionally trying to buck the system, but keeping each song down to 3:14 just didn’t work for us. We realized that the audience was a big part of what we did, which couldn’t be duplicated in a studio. A light bulb finally went off: We needed to make a live album.”

The Allman Brothers Band first played New York City’s renowned Fillmore East on Dec. 26, 1969, opening for Blood, Sweat and Tears. Fillmore impresario Bill Graham loved the group, and in January 1970, they opened four shows for Buddy Guy and B.B. King at Graham’s Fillmore West in San Francisco, returning to the Fillmore East a month later to open three nights for kindred spirits the Grateful Dead. The Fillmore dates were critical to establishing the ABB on both coasts and building a wider, more sophisticated audience attuned with its musical ambitions, and when the group again returned to the Fillmore East in March 1971, it was with producer Tom Dowd and a mobile recording truck in tow.

The original two-record incarnation of At Fillmore East, released by Capricorn in July 1971, cherry-picked material from across all four concerts, commencing the festivities with a loping version of “Statesboro Blues” culled from the first of two March 13 sets. In 2014, Mercury Records released the multi-disc set The 1971 Fillmore East Recordings, presenting all four shows in their entirety: The version available via KORD hails from the second March 13 show, and if it sounds appreciably different from the performance included on the now-familiar 1971 collection, it should — the Allmans may have played many of the same songs from night to night (or even within the same night), but they never played them the same way twice. All four recorded Fillmore East versions of “Statesboro Blues” are absolutely dynamic: Duane’s beloved 1958 Tobacco Sunburst Les Paul (which you hear in the left channel) shrieks and soars like a bird of prey in flight, and Dickey Betts (right channel) responds with a pair of snarling solos conjured from his 1957 Les Paul Goldtop. Gregg’s rueful, preternaturally wizened vocals and soulful Hammond B-3 are no less vital to the Allmans’ version of “Statesboro Blues,” which also boasts a clever stop-time motif at the beginning of each verse, mirroring the song’s opening notes.

Further bolstered by incendiary renditions of Allman touchstones like “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed” and “Whipping Post,” At Fillmore East hit retail as a double album “people-priced” for the cost of a standard single-LP release. While the Allmans’ two previous albums struggled to reach the charts, the live set caught fire within a matter of days, peaking at number 13 on Billboard‘s Top Pop Albums chart and moving more than half a million units by October.

The success of At Fillmore East was profoundly bittersweet, however. By the time the album dropped in July 1971, the Fillmore East itself was no more, with the Allman Brothers Band playing the venue’s closing show on June 27. Even more heartbreaking, Duane Allman died Oct. 29, 1971 from massive internal injuries suffered when he was thrown from his Harley-Davidson Sportster motorcycle, which landed on top of him and skidded another 90 feet with his body pinned beneath it. A little more than a year later, Berry Oakley suffered a fatal motorcycle mishap of his own. The Allman Brothers Band somehow soldiered on, notching its first and only Top Ten hit in 1973 with Betts’ classic “Ramblin’ Man,” and continuing in fits and starts until 2017, when in a matter of months Butch Trucks died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound and Gregg Allman succumbed to liver cancer.

“Statesboro Blues,” meanwhile, was selected for preservation in the National Recording Registry in 2015. In an accompanying essay, Library of Congress sound recording cataloger Brian Bader writes “‘Statesboro Blues’ is like Eric Clapton and Cream’s ‘Crossroads,’ which is a Robert Johnson tune in name only. Both are pre-war blues chestnuts interpreted but not replicated by electric guitarists with considerable talent. An English singer-songwriter and guitarist, whose birth name is Ralph May, was so stricken by McTell and ‘Statesboro Blues’ that he adopted the name Ralph McTell. And no less than Bob Dylan penned a song named after Blind Willie McTell with each verse ending in the refrain: ‘No one can sing the blues like Blind Willie McTell.’ Inspiration and testimony of such an order assures that McTell and his ‘Statesboro Blues’ deserve a place of honor in American popular music.”

Statesboro Blues (KORD-0038)

Related songs: