James Gang’s “Funk #49” represents the platonic ideal of a classic rock song. The trio of Jim Fox, Dale Peters and a pre-Eagles Joe Walsh turned what was originally a spontaneous soundcheck jam into a monster groove, and while “Funk #49” might not have the cultural clout of a “Free Bird” or a “Stairway to Heaven,” it endures across the decades as a bonafide AOR standard.

- /songs/5aI5a552b8e

James Gang’s most recognizable member might have been frontman Walsh, but its origins start with Fox, the group’s namesake and only consistent member. A native of Cleveland, Ohio, Fox received a musical education at the city’s Music School Settlement, and went on to play with a plethora of amateur teen bands. “There were a series of them, none rock and roll to begin with, and no names recalled. Heck, I’m not even sure we had names!” Fox said in a 2017 interview with Perfect Sound Forever. The common thread linking the acts was a focus on standards like Rodgers and Hart’s “Dancing on the Ceiling,” R&B hits and blues, but when Beatlemania made landfall in the U.S., Fox permanently shifted his interest toward the music of the British Invasion.

In 1963, Fox teamed with high school classmates to perform under the moniker Tom King and the Starfires. He left the group to attend college, just weeks before the Starfires signed to Capitol Records, changed their name to the Outsiders, and reached number five on the Billboard Hot 100 with 1966’s “Time Won’t Let Me.” When the Outsiders’ drummer was drafted in the middle of recording their first album, Fox came back long enough to finish the session and go on tour, and upon returning to campus, he was inspired to form his own band.

James Gang started as a five-piece band mixing Fox’s schoolmates and friends with established Cleveland musicians including lead guitarist Glenn Schwartz, who beat out a rotating list of players including Greg Grandillo (later of Rainbow Canyon) and John “Mouse” Michalski, who as a member of the Count Five scored his own Top Ten hit via 1966’s “Psychotic Reaction.” The James Gang roster remained in permanent flux, with members dropping out either from disinterest or because of the military draft, and the final lineup wouldn’t solidify until May 1968, months after Schwartz’s friend Walsh expressed interest in joining the group.

The 20-year-old Walsh had recently left the Measles, which he formed at Kent State University in 1965; the group would go on to secretly record two tracks for the Ohio Express’ debut album, ironically named Beg, Borrow and Steal. When Schwartz set out for California in late 1967, Walsh lobbied Fox for an audition. “He would not go away! I looked through the peephole in the door to my apartment at Kent State, and he would not go away,” Fox joked to Cleveland classic rock station WCNX in 2011. Walsh made the cut, and after a handful of additional lineup changes, the James Gang was set to open for Cream at Detroit’s Grande Ballroom when rhythm guitarist Ronnie Silverman pulled out at the last moment. Walsh, Fox and bassist Tom Kriss hit the stage as a trio, and the overwhelmingly positive response cemented the final lineup.

Following a bevy of gigs and the arrival of manager Mark Barger, James Gang signed to Bluesway Records, an imprint of ABC Records, at the top of January 1969. The person who signed them was producer Bill Szymcyzk, who had built a name for himself as an engineer at Manhattan’s Brill Building, the famed songwriting and production incubator responsible for countless post-war pop hits. Szymczyk desired a larger creative role, so he took a pay cut to work as a producer at ABC, which also gave him license to sign bands to its subsidiary labels after he successfully reinvented the sound of B.B. King via the 1969 albums Live and Well and Completely Well (the latter featuring the blues guitar great’s signature song, “The Thrill Is Gone”). “Once I’d had success with B.B., the record company said ‘Maybe you do know what you’re doing,’” Szymcyzk said in an interview with Tape Op.

Szymcyzk claimed he signed the James Gang without knowing they were a trio; Walsh’s playing, in particular, piqued his interest. Szymczyk oversaw the band’s first record, 1969’s Yer’ Album, which featured covers of Buffalo Springfield’s “Bluebird” and the Yardbirds’ “Lost Woman” but mostly centered around the trio’s proclivity for drawing songs from jams. One such song, “Funk #48,” serves as a de facto prequel to “Funk #49” –– the tempo and key, along with Fox’s syncopated kick drum and Walsh’s bluesy guitar riff, make them obvious aural kin.

One critical difference: “Funk #49” features Dale Peters on bass. After the release of Yer’ Album, Kriss erupted and quit the James Gang. “He just spilled his guts,” Fox recalled to Ultimate Classic Rock. “Hadn’t said shit in six months… Joe and I were blindsided.” Peters, yet another Fox acquaintance, was on the outs with his current band, the Case of E.T. Hooley; Fox invited him to a post-gig jam, and the chemistry was evident from the get-go. “It was instantaneously an upgrade, which we never expected,” said Fox.

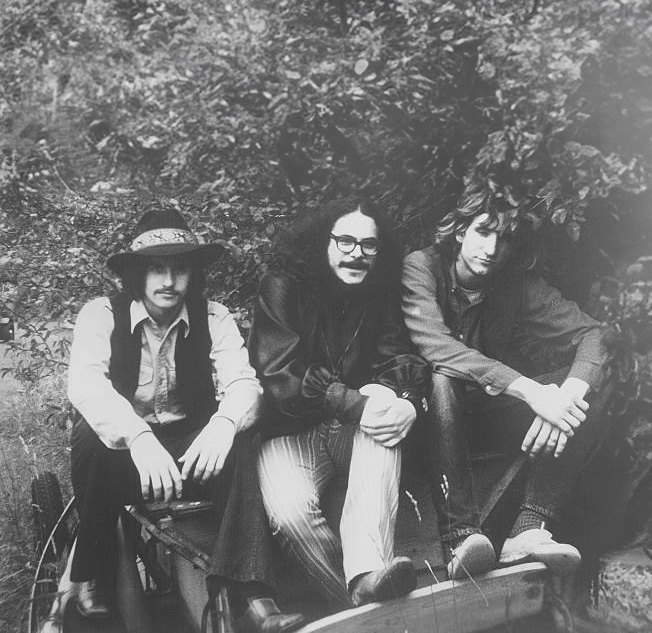

“Funk #49,” the biggest hit from their 1970 sophomore album James Gang Rides Again, stems from a warm-up jam the trio used to play at soundcheck, and it defines their capacity to turn improvisation into indelible rock music. Walsh’s shadow looms large over the James Gang catalog in general, but on “Funk #49,” his parts arguably function more as accessories to Fox’s drumming, the real star of the show here. Walsh’s guitar line is panned hard to one speaker, and his voice is relegated to six slight lines of lyrics over three verses. Fox, in comparison, fills the ears with constant drum fills, kicks on the off-beat, and unleashes a 40-second solo breakdown featuring seven different kinds of percussion (see KORD’s liner notes for the complete list).

On the other side of the rhythm equation, “Funk #49” demonstrates Peters’ seismic impact on the James Gang sound. Listen to “Funk #48” and “Funk #49” side by side: Kriss’ bass playing on the former feels at odds with Walsh’s riff, and his solo notes don’t line up in the pocket alongside Fox’s hits. Peters’ contributions to “Funk #49” are not only more inventive (check out the twin bass lines that emerge and harmonize throughout the track), but he syncs up in lockstep with Fox’s beat on the verses and with Walsh’s refrain lick in-between them. Crucially, Peters drops out completely for Fox’s percussion-heavy solo, signifying an instinctual understanding of his role in the trio.

Walsh’s “Funk #49” vocals are adequately charismatic, but Fox remembers him expressing serious reservations about his role in front of the mic. “He said, ‘Look, I’m not fooling anyone –– I have an odd voice. I think I might be stronger concentrating on the instruments. Who do you know?’” Who Fox knew was still one more schoolmate, vocalist Kenny Weiss, who joined the James Gang before the Rides Again sessions. The plan was to allow Walsh more breathing room to play guitar, but Weiss only contributed vocals to a handful of tracks (produced for George Englund’s movie Zachariah) before he was ousted. Weiss sued the James Gang for $50 million; Szymcyzk agreed to produce Rides Again for free if the parties settled out of court, and they did — for a few hundred dollars.

James Gang were not known for being chart titans: “Funk #49” stalled at number 59 on the Hot 100, and their only other chart entry, “Walk Away” (from 1971’s Thirds), peaked at number 51. They did, however, benefit from a shift in radio that allowed their songs to enter the public consciousness much more easily. By the late 1960’s, the Federal Communications Commission successfully mandated that FM radio stations, which were largely simulcasting programming from their AM counterparts, switch to original programming instead. In order to keep the original programming inexpensive, many FM radio DJs adopted the free-form programming philosophies of college radio stations, which insisted on spinning deep cuts and full-length LPs instead of Top 40 singles. Though their programming was originally genre-diverse and less commercial, these DJs tended to prefer airing rock music for its perceived sophistication compared to the era’s pop music, a practice that spawned the term “progressive rock.”

The resulting format, AOR (for “album-oriented rock”), was soon adopted by mainstream radio stations like Boston’s WMMR and Cleveland’s WMMS, who sanded down the more controversial elements of the programming and hyper-focused on rock in order to attract advertisers. By the dawn of the 1970s, AOR had become a staple of the American airwaves, and as consumer adoption of FM radios surged, the format grew to immense popularity. This allowed rock acts like James Gang far more exposure (and inspired more devout audience interest) than what the trio’s middling chart success would suggest, and “Funk #49” morphed into a staple of the format.

Unfortunately, the group wouldn’t experience the benefits of this effect until it was too late. After Thirds, James Gang managed one more LP, Live in Concert, before Walsh –– who was crumbling under the pressure of fronting the band –– finally decided to depart. He left for Colorado and formed another trio, Barnstorm, with multi-instrumentalist (and future Eagles associate) Joe Vitale and bassist-for-hire Kenny Passarelli. In a blow to James Gang’s prospects, Szymczyk followed Walsh out west, establishing a musical power couple that would later join forces on one of the best-selling records of all time, the Eagles’ Hotel California.

Fox and Peters attempted to carry on, recording 1972’s Straight Shooter with singer Roy Kenner and guitarist Domenic Troiano (later to join the Guess Who) before cutting a pair of LPs with guitarist Tommy Bolin, who went on to join Deep Purple. Those efforts failed to match the power of the material on Rides Again, especially “Funk #49.”

“I thought we would be at it for a long time,” Fox admitted to Ultimate Classic Rock. “That was it — [Rides Again] was the great James Gang album. Period.”

- /songs/5aI5a552b8e