Billy Griffin remembers what it was like at the peak of his music career, when he was an eligible bachelor dating Hollywood starlets. “I would get in my car… and I knew when the girl sat down, I could say ‘You wanna hear my record?’ and I would just turn on the radio. ‘Love Machine’ would come on. Every channel. That is a hit.”

A hit it was. At 4.5 million records sold, 1975’s “Love Machine” was the biggest single of the Miracles’ career, and Griffin, who became the group’s lead singer following Smokey Robinson’s departure, goes so far as to argue that it was Motown’s biggest-selling release ever. (He reasons there were so many different kinds of media at the time — cassette, cassette single, eight-track, LP and the 45 — that some people would have purchased the track in more than one format.) Though Griffin’s assessment may be purely anecdotal, “Love Machine” is nonetheless one of the most widely-known records ever put out by the label. It has been covered by the likes of Wham! and Thelma Houston, sampled by Drake and, according to Griffin, it’s the Motown song most used in film, television and commercials, generating more than $15 million in revenue.

Technically named “Love Machine (Part 1)” — the nearly seven-minute-long track was split in two for single release — it was only the second number one hit for the Miracles, the first being 1970’s “Tears of a Clown,” sung by Robinson with music composed by labelmate Stevie Wonder. Not only did “Love Machine” herald a new direction for the Motown quartet, it was one of the earliest songs of the disco era, cementing the label’s reign in the new genre.

Nineteen-year-old Baltimore native Griffin was introduced as the Miracles’ new lead singer in July 1972, during the final stop on Robinson’s six-month farewell tour with the group he founded 17 years earlier. After auditioning scores of new singers, Griffin was chosen in part because he also wrote songs: Robinson had composed most of the Miracles’ catalog up to that point, but now he wanted to devote more time to his young family and to his role within Motown’s executive suite.

Griffin recalls the audition process not as a commercial calculation by Motown brass, but as an instinctive response from another faction. “I auditioned after 50 guys… and the Miracles’ wives, they said ‘That guy,’” Griffin told UBN radio show We Luvv Rare Grooves.

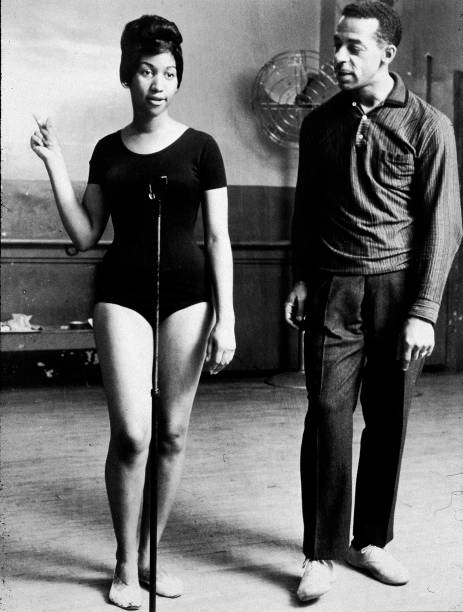

After the wives fell for the baby-faced teen with the silky falsetto, Griffin wasted no time applying his youthful energy to the Miracles’ image. “The first thing I did was get them out of those toreador suits,” he said. He instead favored the Super Fly look: wide-brimmed hats, bell-bottomed trousers and long blazers with wide lapels. Griffin’s makeover didn’t stop at the sartorial, however. He made the balding Ronnie White wear a wig, and insisted on a girdle for Bobby Rogers until the tenor lost some weight. To complete the transformation, Griffin and the Miracles’ stage manager Cholly Atkins got to work on dance routines inspired by the Temptations’ modern choreography.

Though the changes may have seemed drastic, the extant Miracles were amenable to the group’s new direction. “Bobby, Ronnie and Pete (Moore) were very agreeable to making a change,” Griffin said, “[because] people would now see them as individuals, as opposed to Smokey’s background singers.”

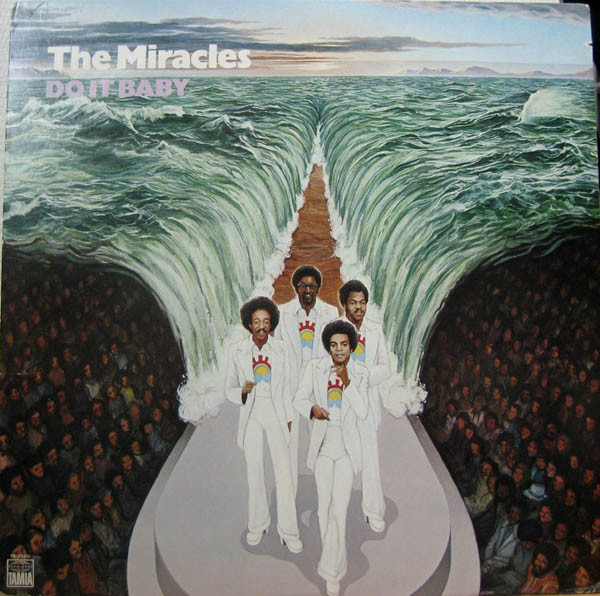

The first album with the new Miracles lineup was 1973’s aptly-named Renaissance. Robinson executive-produced, assisting the group’s rebirth by deploying the full force of the Motown hit machine. “They hired every great writer that Motown had, then they hired eight producers, and it was a competition to come up with a single,” Griffin recalled. The funky, up-tempo “What Is a Heart Good For” was released as the first single, then withdrawn in favor of the ballad “Don’t Let It End (‘Til You Let It Begin).” Neither song cracked the upper half of the Billboard Hot 100, but despite its lack of cohesion and the absence of a signature sound, the Miracles were happy with Renaissance and its new direction, and set about recording their next LP, 1974’s Do It Baby, whose title track would get them one step closer to a smash hit.

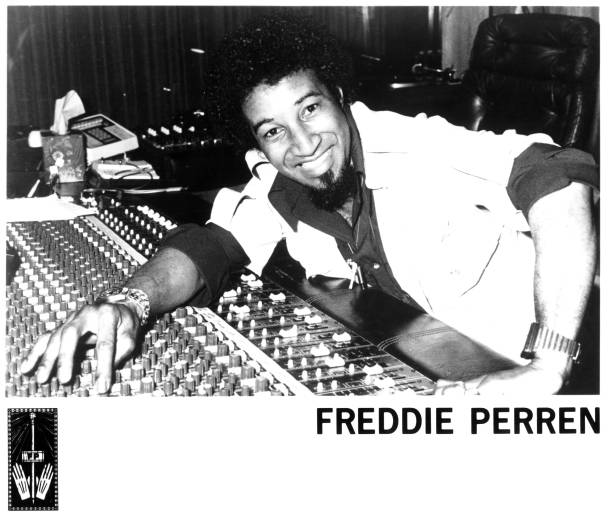

“Do It Baby,” written by husband-and-wife Motown staff songwriters Freddie Perren and Christine Yarian, peaked at number 13 on the Hot 100 in October 1974. With Perren producing and members of the legendary Funk Brothers backing, the song typified the Miracles’ move toward a dance-oriented sound. “Do It Baby” also signaled a turn toward more overtly sexual lyrics, apropos for a decade of hedonistic excess. A third album with the new lineup, the lackluster Don’t Cha Love It, was written almost entirely by Perren and Yarian and released in early 1975. Although the title track reached number 78 on the pop charts, the album stagnated, and Griffin began planning the Miracles’ next project, one on which he would take greater creative control.

City of Angels, which Griffin calls a “black soul opera,” was the result. “The seed for the idea came one day when I was looking out of the window at a Holiday Inn in Hollywood, thinking about all the people who must come here with aspirations of making it,” Griffin is quoted in The Motown Encyclopedia. Griffin went to Moore with the idea, and the two began to contemplate the tragic side of the Hollywood fairytale: all of the people whose dreams are never realized.

City of Angels, written entirely by Griffin and Moore, tells the story of a young man who follows his estranged girlfriend to L.A. in her quest for Hollywood stardom. In a Tinseltown twist of fate, he’s the one who becomes famous, and “Love Machine” is his self-mythologizing moniker after he becomes a screen idol.

Though the success of City of Angels lies largely with co-writers Griffin and Moore, credit must also be given to the session musicians who played on the album. Bassist Scott Edwards told Songfacts that because co-producers Perren and Moore lacked expertise with some of the instruments, they relied on the players to flesh out their parts in the studio.

“We actually were writers and composers… because the things that we came up with, the arrangers and the producers were nowhere in that direction for our particular instruments. A lot of the hits were basically the musicians jamming,” Edwards explained. “The same thing happened with ‘Love Machine.’ We were just jamming, and Freddie said ‘Do the changes to these chords.’ So that’s the way a lot of stuff was made.” Indeed, Edwards’ melodic, driving bass line keeps the track percolating throughout, and though it’s low in the mix, it undergirds “Love Machine” with a joyful spontaneity — the loose feel of the jam session remains.

That loose feel extends to the lyrics. While Robinson’s songwriting is known for its clever wordplay and universal tales of love and longing, “Love Machine” is a goofy bag of mixed metaphors and libidinous growls: it’s hard to imagine Smokey singing lines like “My chassis fits like a glove/I’ve got a button for love” or borrowing inspiration from the likes of Sly and the Family Stone (Griffin said he stole Bobby Rogers’ oo-oo-ooh-yeah from “Hot Fun in the Summertime”). Despite its departure from the classic Miracles sound, “Love Machine” is undeniably catchy, danceable and over the top in a way that only a Seventies disco song can be, and its immense staying power has extended the group’s career to this day.

Griffin tells another story about his “Love Machine” heyday, this one about the time he and a friend crashed a New Year’s 1976 party at a sophisticated Newport Beach hotel. “A minute after ‘Auld Lang Syne’ is finished, the band kicks in to ‘Love Machine.’ My buddy says ‘Hey man, let’s go tell them who you are.’” Griffin declined. “I just laid back on the wall and watched all those people dancing to my song. Man, there’s nothing like that.”

Related Songs

- /songs/50225a2136a22504