This KORD Interactive Playlist commemorates the career of Motown Records’ longtime backing vocal trio the Andantes, spotlighting their role in landmark hits by the Supremes, Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye and others. You can use the stem player to isolate or mute the Andantes’ enchanting, gospel-inspired harmonies, or deconstruct each song any other way you wish.

All songs are presented in chronological order to underscore the relentless evolution of the Motown Sound. This playlist will continue to grow as we add new songs and stories, so check back often.

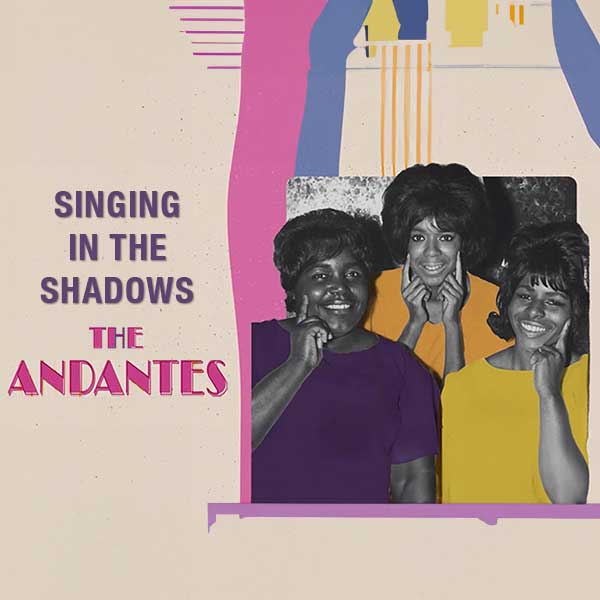

You may not know the Andantes by name, but you’ve heard their voices for years. The trio of Marlene Barrow, Louvain Demps and Jackie Hicks served as Motown Records’ in-house backing vocalists throughout the company’s heyday, singing on thousands of sessions between 1962 and 1972, including at least seven number-one pop hits.

“The Andantes were three of the greatest singers ever in life,” according to Smokey Robinson, who incorporated the group into many of his Motown efforts. “Any one of them could have been a lead singer or solo artist.”

Motown never formally credited the Andantes until the group’s name appeared on the back cover of the Supremes’ Robinson-produced 1972 LP Floy Joy. But scholars and fans have helped bring their contributions to light, and like their counterparts in the Funk Brothers, the label’s nonpareil studio band, the Andantes are now celebrated as a cornerstone of the Motown Sound.

Hicks (first alto) and Barrow (second alto) formed the Andantes with soprano Emily Phillips. All three grew up singing in the choir of Detroit’s Hartford Avenue Baptist Church under the tutelage of pianist and vocal coach Mildred Dobey, who later gave the Andantes their name, telling them it meant “soft and sweet.”

When pianist and songwriter Richard “Popcorn” Wylie auditioned for Berry Gordy Jr.’s fledgling Motown label in 1959, he brought the Andantes to back him; Gordy passed on Wylie, but invited the Andantes back to audition on their own. Family commitments led Phillips to resign from the group soon after, and Motown suggested Barrow and Hicks replace her with Demps, a soprano already under contract with the label as a member of the Rayber Voices, a backing group whose members also included Gordy’s second wife, Raynoma, as well as Brian Holland, later one-third of the celebrated Holland-Dozier-Holland writing and production team. The Rayber Voices most notably contributed backing vocals to Barrett Strong’s 1959 single “Money (That’s What I Want),” the Motown enterprise’s very first hit.

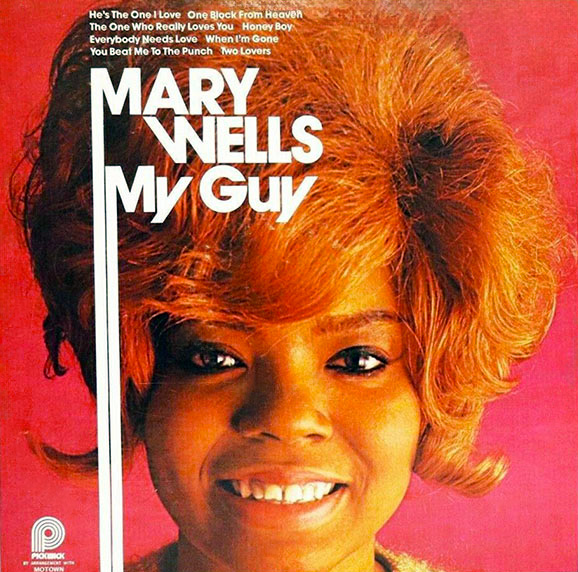

“I cannot remember the very first time I heard myself on the radio,” Hicks said in 2021. “It might be ‘My Guy’ by Mary Wells… that was our first million seller.”

My Guy (1964)

Wells, Motown’s first solo female star, played a vital role in the label’s development. She joined Motown at the age of 17, cornering Gordy at Detroit’s Twenty Grand club to pitch a song she wrote for Gordy’s associate Jackie Wilson to sing. Gordy instead enlisted Wells to record it herself, and in September 1960 Motown released the blistering “Bye Bye Baby,” which reached the Top Ten on the Billboard R&B chart and crossed over to number 45 on the Hot 100. Wells followed “Bye Bye Baby” with a succession of hits written and produced by Smokey Robinson, beginning with 1962’s calypso-inspired “The One Who Really Loves You” (which swiveled its hips all the way to the number two spot on the R&B chart and number eight on the Hot 100) and continuing with a pair of R&B number ones, “You Beat Me to the Punch” (which made her the first Motown star to receive a Grammy nomination) and the million-selling “Two Lovers.”

Wells and Robinson reunited for “My Guy,” released Mar. 13, 1964, and together they created an absolutely flawless pop record — a beguiling declaration of love and loyalty crafted with endearing sincerity and effortless sophistication. If you’ve never paid close attention to the Andantes before, you can’t mistake their presence here: the trio’s call-and-response vocals chime like crystal bells.

“My Guy” was Motown’s third number-one pop hit, spending two weeks atop the Billboard Hot 100 (sandwiched between Louis Armstrong’s “Hello, Dolly!” and the Beatles’ “Love Me Do”). Its success earned the Andantes a $500 bonus: “That was the first bonus we ever got,” Demps stated in an interview for The Complete Motown Singles series.

But “My Guy” was Wells’ final solo single for the label. On her 21st birthday, she exercised an option to terminate her Motown contract and signed with 20th Century Fox, where the hits dried up. “In 1964, Mary Wells was our big, big artist,” Loucye Gordy Wakefield, Motown’s first sales chief, told The New York Times in 1992 after the 49-year-old singer died of cancer. “I don’t think there’s any audience with an age of 30 through 50 that doesn’t know the words to ‘My Guy.’”

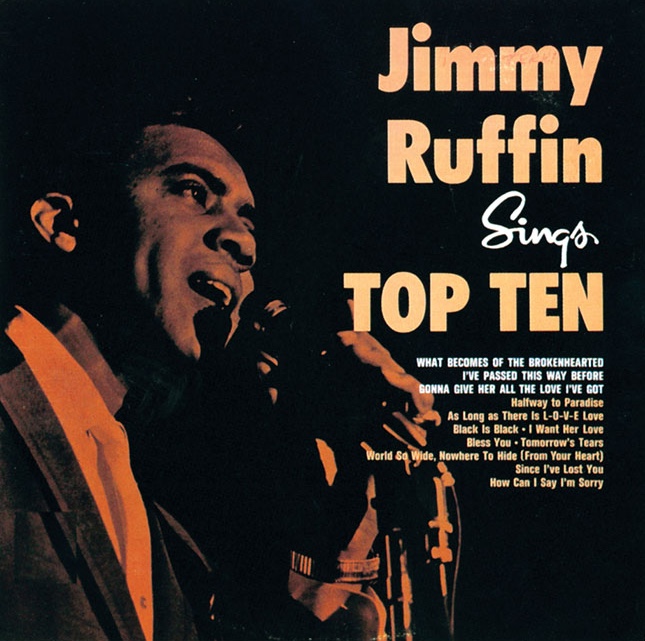

What Becomes of the Brokenhearted (1966)

Jimmy Ruffin, the older brother of the Temptations’ David Ruffin, first entered Motown’s orbit after Raynoma Gordy caught his performance at Muskegon, Mich.’s Ebony Club and signed him to the company’s short-lived Miracle imprint (tagline: “If it’s a hit, it’s a Miracle!”) to headline the 1961 single “Don’t Feel Sorry for Me.” Ruffin’s fledging recording career screeched to a halt when he was drafted into the U.S. Army, and by the time he returned to Motown in 1964 to cut the Norman Whitfield-produced “Since I’ve Lost You,” the label was a cultural phenomenon. The single went nowhere, however, and the follow-up “As Long as There Is L-O-V-E Love” stalled at number 120 on the Billboard pop chart.

Motown staff writers James Dean and William Weatherspoon originally earmarked “What Becomes of the Brokenhearted” for the Spinners, but its soul-shattering evocation of lost love stopped Ruffin in his tracks, and he claimed the song for his own. Dean and Weatherspoon completed the lyrics and added a spoken-word introduction, and on Nov. 9, 1965, Ruffin recorded his lead vocal under the auspices of Weatherspoon and co-producer William “Mickey” Stevenson. In addition to the Andantes, the backing vocals feature the Originals — Freddie Gorman, Walter Gaines, Hank Dixon and Joe Stubbs — in their Motown debut; the female voices mostly float high above Ruffin’s lead, while their male counterparts provide counterpoint responses to the lyrics. Strings were added on Feb. 23, 1966 courtesy of Paul Riser, whose magisterial arrangement elevated the material from pathos to poetry, and earned him a co-author credit.

Motown executives couldn’t make heads or tails of “What Becomes of the Brokenhearted,” however, and rejected no fewer than 13 different mixes. “They sat on it forever,” Ruffin recalled in an interview for The Complete Motown Singles | Vol. 6: 1966. “And the spiel that I did on the beginning of it, they took that off. That’s why there’s such a long introduction. They didn’t think a Black guy could sell this.” Motown engineer Harold Taylor finally cracked the code: his third stab at mixing “What Becomes of the Brokenhearted” earned Berry Gordy’s thumbs-up, and the single appeared on the Soul imprint on June 3, 1966, reaching number seven on the Billboard Hot 100 and climbing to number six on the R&B charts. It was the biggest hit of Ruffin’s career, and allowed him to quit his job on the Ford Motor Company assembly line.

“Jimmy Ruffin was a phenomenal singer,” Gordy said in the wake of Ruffin’s 2014 passing, going on to proclaim “What Becomes of the Brokenhearted” “one of the greatest songs put out by Motown, and also one of my personal favorites.”

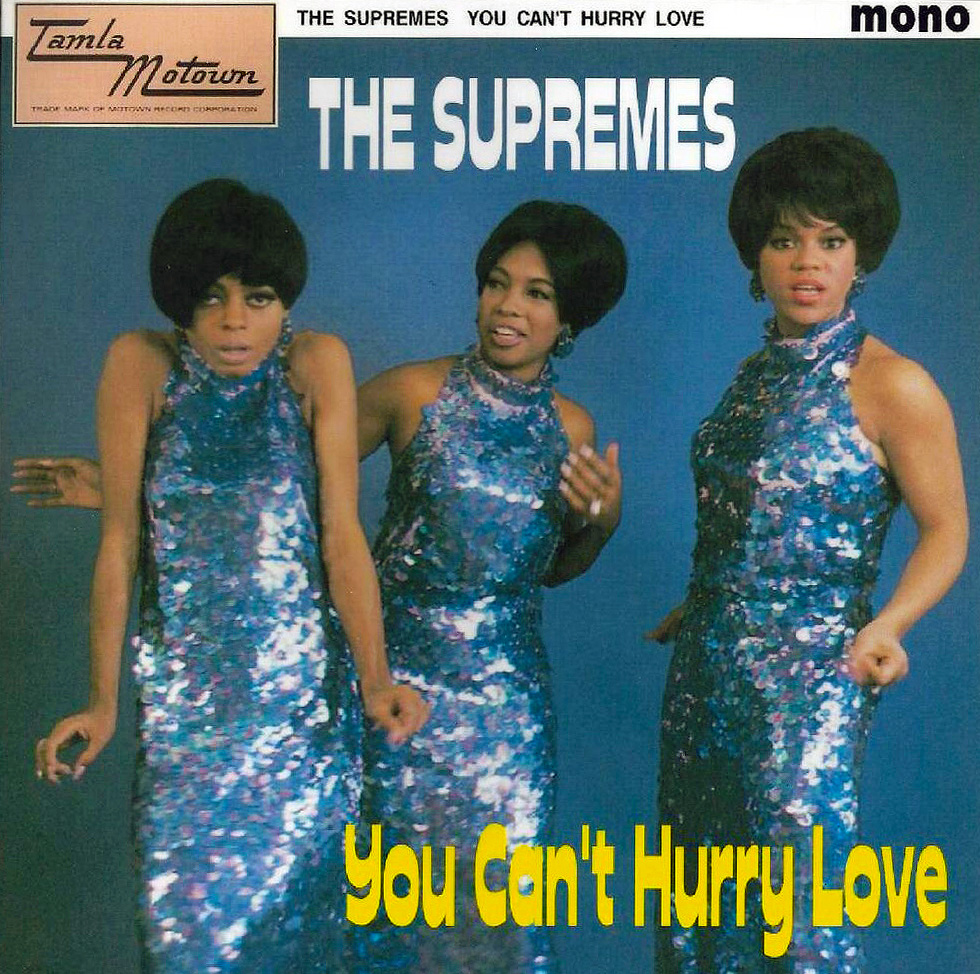

You Can’t Hurry Love (1966)

Sometimes the Andantes supplied more than backing vocals. When the Supremes’ Florence Ballard did not participate in the session that produced “You Can’t Hurry Love,” she was surreptitiously replaced by Marlene Barrow, a substitution that did absolutely nothing to dull the single’s impact or slow its ascent to the top of the charts.

The Andantes first teamed with the Supremes on “Stop! In the Name of Love,” a Billboard pop number one in the spring of 1965. The talented but troubled Ballard was growing increasingly disillusioned with success, however: although most onlookers considered her the strongest singer within the Supremes, Motown made Diana Ross the lead vocalist, which destroyed the group dynamic. As Ballard’s battle with depression deepened, she turned to alcohol, and began missing recording sessions and live performances. Berry Gordy turned to Barrow to fill the gap: she made her first live appearance alongside Ross and Mary Wilson on June 18, 1965 at a debutante ball in the Detroit suburbs, and continued substituting for Ballard on a series of one-nighters as well as the Supremes’ engagement at Boston’s Blinstrub’s Village, one of the largest nightclubs on the East Coast.

“You Can’t Hurry Love” was developed for the Supremes by Brian Holland, Lamont Dozier and Eddie Holland, the studio masterminds behind 10 of the group’s 12 number-one pop hits. The song borrows liberally from “(You Can’t Hurry God) He’s Right on Time,” written and recorded by Dorothy Love Coates of the Original Gospel Harmonettes. The exact circumstances behind Ballard’s absence from the “You Can’t Hurry Love” studio sessions are unclear, but according to the expanded reissue of the Supremes A’ Go-Go LP, all vocals for the track were cut on July 5, 1966, a date when Ballard was known to be on a leave of absence. Motown was mum on the subject when “You Can’t Hurry Love” dropped three weeks later; you can isolate the vocals here in KORD to hear Barrow and Wilson singing almost exclusively in unison, providing support and counterpoint to Ross’ lead performance.

The Andantes remained fixtures on Supremes sessions even after Ballard was ousted in mid-1967, and when Ross stepped out in 1970 to launch a solo career, she took the Andantes with her. But more on that later.

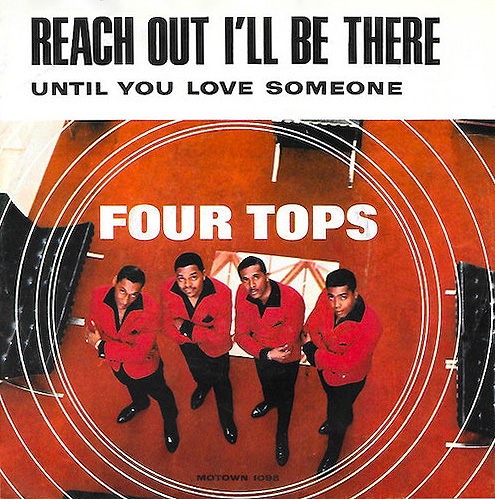

Reach Out I’ll Be There (1966)

“Reach Out I’ll Be There” is a light in the darkness — an achingly tender declaration of commitment and compassion delivered with the force of rolling thunder. Released in August 1966 following a summer of mounting civil unrest and violent rebellion, the Four Tops’ humanist anthem remains a bottomless reservoir of strength and succor through all times of turmoil, its physical and emotional impact unmatched across the Motown canon. “To me, it felt like a chant, almost religious — a song of hope for the world,” the group’s Duke Fakir proclaimed nearly half a century after the single stampeded to the top of the Billboard charts.

The Four Tops were established veterans of the supper club circuit when they signed to Motown in April 1963, and when Gordy paired the group with the Holland-Dozier-Holland triumvirate, the resulting “Baby I Need Your Loving” climbed to number 11 on the Billboard Hot 100, selling more than a million copies. “Reach Out I’ll Be There,” the first of 12 tracks completed for the Four Tops’ fourth Motown album, Reach Out, represents the pinnacle of the H-D-H aesthetic. Dozier told The Wall Street Journal he set out to “create a mind trip — a journey of emotions with sustained tension, like a bolero. To get this across, I alternated the keys, from a minor, Russian feel in the verse to a major, gospel feel in the chorus.” The Andantes, the not-so-secret weapon on no fewer than 16 Four Tops singles over the years, were essential to Dozier’s grandiose ambitions: isolate the “Reach Out I’ll Be There” vocals in KORD to hear them sing in unison with the Four Tops during the verses, then part ways during the choruses.

“Reach Out I’ll Be There” topped the Hot 100 for two weeks, spending the same period of time at the summit of the R&B charts. It was also the second Motown single to reach number one on the U.K. pop charts, two years after the Supremes’ “Baby Love.” Bristol, England-born Adam White, later a senior executive at Universal Music Group, was a typical 19-year-old Motown fan when “Reach Out I’ll Be There” first materialized at radio. “I couldn’t believe this extraordinary music was coming out of that car radio speaker,” White recalled to Gerald Posner, author of the book Motown: Music, Money, Sex and Power. “It’s a moment I can never forget. That’s the power Motown music had then. It was simply the most dynamic, vibrant music I ever heard.”

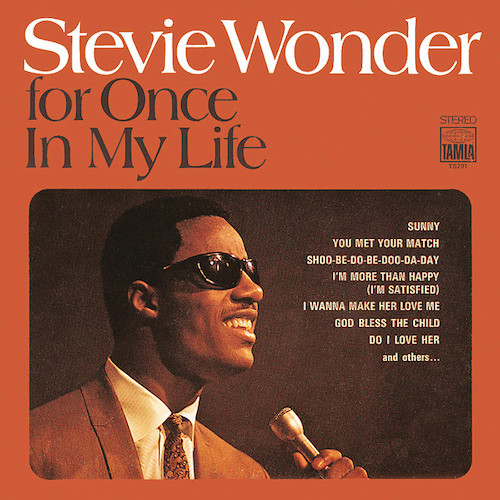

For Once in My Life (1968)

It doesn’t matter who sings a song first — only who sings it best. “For Once in My Life” passed through more hands than a church collection plate before it finally landed with Stevie Wonder, who delivered an instant pop standard.

Writers Ron Miller and Orlando Murden initially envisioned “For Once in My Life” as a slow, earnest ballad, and its earliest documented renditions remained true to those intentions. That changed in the summer of 1967, when producer Hank Cosby (a founding member of the Funk Brothers) assigned the song to 17-year-old Wonder, whose meteoric recording career was entering a new, more mature phase.

“I said ‘Stevie, I love this song, and I think it hasn’t been recorded properly, because everybody sings the song like they’re dying [or] they’re crying — like they’re hurting. I thought ‘You’re supposed to be happy! You found somebody who loves you,’” Cosby told BBC Radio 1’s Stuart Grundy in 1977. “So we recorded the song, and I thought it came out great — so much fire, so much feeling — but when Ron Miller heard I had jazzed the song up, he went crazy! He went berserk! He said ‘What have you done to my song?! Oh my god!’ So the song laid on the shelf for one year. Nobody liked the song but Stevie and I. But anyway, [Motown] finally released the song, because there was no product on the shelf. As soon as the song was out, we knew it was a hit. Automatic hit. Straight to the top. [Miller] said ‘Oh, yes, I knew it all the time.’ He loved it after that.”

What’s not to love? Cosby’s instincts were resoundingly correct: Wonder’s innate energy and joy transformed “For Once in My Life,” making it the song it was always meant to be. The single, which features the Andantes and the Originals combining for pitch-perfect seven-part harmonies, rocketed to number two on Billboard’s pop and R&B charts following its Oct. 15, 1968 release, but it could not dethrone the recording sequenced next.

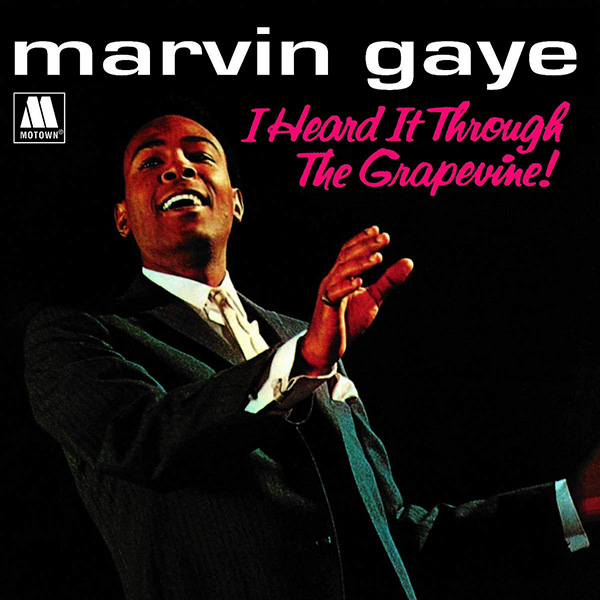

I Heard It Through the Grapevine (1968)

Marvin Gaye’s “I Heard It Through the Grapevine,” the confessional account of a man devastated to learn through the rumor mill of his lover’s infidelity, signaled a decisive departure from Motown classics past. Producer Norman Whitfield, who wrote the song in partnership with Barrett Strong, eschewed the ebullient R&B grooves that propelled the label’s commercial ascension in favor of something deeper, darker and more daring, and found the perfect vessel for his vision in Gaye, the gifted hitmaker torn between the sensual and the spiritual.

Gaye wasn’t the first Motown act to record “I Heard It Through the Grapevine,” however. Smokey Robinson’s Miracles cut the song in August 1966, although their rendition remained unreleased for two years; moreover, Gaye’s version — recorded over a series of five studio sessions spanning from Feb. 3 to April 10, 1967 — languished in the Motown vaults for 18 months. A fiery third rendition headlined by Gladys Knight and the Pips was the first to earn Berry Gordy’s approval, appearing on Motown’s Soul subsidiary on Sept. 28, 1967 and going on to sell 2.5 million copies.

None of this makes the Gaye version of “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” anything less than definitive. Its innovations begin with Whitfield’s simmering production, which is somehow both spacious and claustrophobic at the same time, perfectly conveying the tortured psyche of a man gasping for air and grasping for terra firma as hopelessness consumes him. The Andantes are a solemn, spectral presence here, their voices hushed like gossip as they alternate between unison singing and three-part harmonies — a stark counterpoint to Gaye’s unbridled anguish. “[Whitfield] set the song in a key that was beyond the singer’s natural range, so that he had to strain to reach the notes,” writes Peter Shapiro in his book Turn the Beat Around: The Secret History of Disco. “The result was the greatest performance of Gaye’s career, unifying all of his gospel training and earthy sensuality in one sustained cry of desperate passion.”

Gaye’s rendition was discreetly tucked away on his 1968 LP In the Groove until E Rodney Jones, a DJ at Chicago’s Black community radio station WVON, grokked its potential and played it on the air. Stations across the U.S. soon added “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” to their playlists, and finally Motown bowed to public sentiment, officially releasing the song as a single on Oct. 30, 1968 — whereupon it became the biggest-selling release in label history (a title usurped in mid-1970 by the Jackson 5’s “I’ll Be There”).

“I loved Marvin, loved recording with Marvin,” Jackie Hicks recalled more than four decades later. “He was a perfectionist, and we enjoyed that with him. Everything just had to be just right for Marvin, and for that we are grateful.”

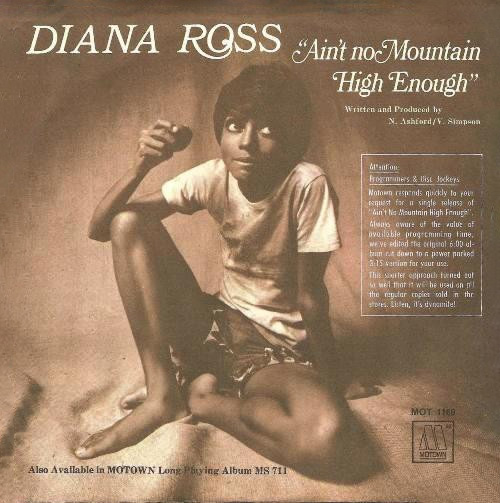

Ain’t No Mountain High Enough (1970)

Gordy first revealed his plans to spin Diana Ross out of the Supremes during a spring 1967 meeting at his Detroit mansion. “Berry spoke openly about making Diana a solo star — a chance [Mary Wilson and Florence Ballard] grudgingly agreed to,” writes Nelson George in Where Did Our Love Go? The Rise and Fall of the Motown Sound. Ballard spiraled deeper into depression and alcoholism in the weeks to follow, however, and when she showed up inebriated ahead of the trio’s July 1967 performance at Las Vegas’ Flamingo Hotel, Gordy dismissed her from the act she co-founded and named as her replacement Cindy Birdsong, formerly of Patti LaBelle and the Blue Belles. Beginning with their next single, “Reflections,” the group was officially renamed Diana Ross and the Supremes, and by 1968, Gordy was actively seeking candidates to replace Ross in anticipation of her first solo recordings.

The Andantes played a central role in the Supremes’ post-Ballard output — just how central we can’t quantify (at least not yet; stay tuned to KORD for updates) — and when Ross cut her self-titled solo debut with writers and producers Nickolas Ashford and Valerie Simpson, she retained custody of the group. You can hear Simpson, the Andantes and others on the heavenly choir electrifying the six-minute symphonic soul epic “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough,” the first of Ross’ six number-one solo smashes.

“Isaac Hayes had started doing all these long records that lasted six minutes instead of three. So everybody was getting on the bandwagon. And we wanted to get on it, too. So we said ‘What song could we stretch that could last that long?’” Ashford explained in an interview for The Complete Motown Singles Vol. 10: 1970. “I loved Diana Ross’ speaking voice. I thought she had a very sexy tone when she talked and when she sang. So we wrote extra lyrics, trying to stretch it out. And Val came up with these new chords. That was one of our best assignments, trying to get that song to where it is. And I think still today, her version just feels like a masterpiece to me.”

The Andantes’ time at Motown concluded when the company cut out for southern California in the summer of 1972. Louvain Demps came close to signing to ABC-Dunhill as a solo act, but when the deal fell through, she moved to Atlanta to work with children with intellectual disabilities, spelling the Andantes’ end. Both Barrow and Hicks pursued lives outside of music, but as the years went by and Motown scholarship advanced, the Andantes’ considerable impact on many of the label’s biggest hits became clearer, and in 1990 Barrow, Hicks and Demps joined with Detroit soul singer Pat Lewis to record new Andantes music for Northern soul producer and DJ Ian Levine’s Motorcity Records. Demps also cut a 1992 solo LP for the label, Better Times. The Andantes were inducted into the Rhythm and Blues Music Hall of Fame in August 2014; Barrow died the following February at the age of 73.

“They were on every song — all the ones that were hits,” Mickey Stevenson said in 2018, adding that if the Andantes were unavailable for a session, he would halt production until the trio could accommodate his request. “If one of them wasn’t feeling well, we would hold that tune until she felt better. I couldn’t have done it without them.”

KORD Interactive Playlist: The Andantes

KORD Interactive Playlists leverage the app’s stem player to explore pop music history in a whole new way. Each playlist supplies the technological capabilities and narrative context to fully appreciate the contributions of music’s unsung heroes: the virtuoso session players, producers, songwriters and arrangers behind the superstars.