This KORD Interactive Playlist commemorates the career of Aston “Family Man” Barrett, the longtime bassist for reggae pioneers Bob Marley and the Wailers. You can use the stem player to isolate or mute Barrett’s booming rhythms, or deconstruct each song any other way you wish.

All songs are presented in chronological order to underscore the evolution of Barrett’s approach. This playlist will continue to grow as we add new songs and stories, so check back often.

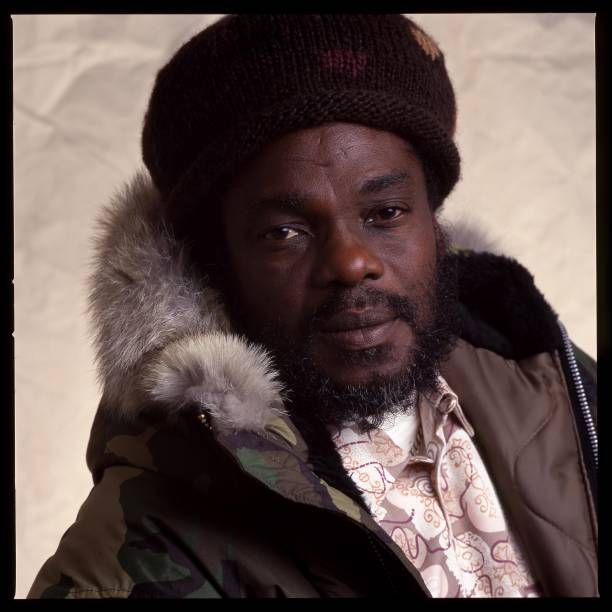

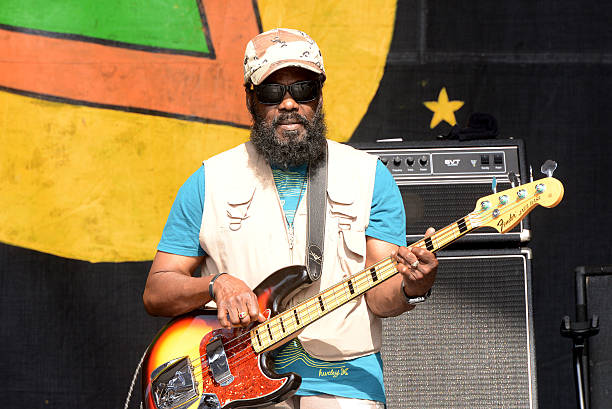

Aston “Family Man” Barrett elevated the low end to unprecedented heights. His emphatic approach to bass guitar ripples across reggae history like a seismic tremor, grounding and galvanizing a series of now-classic recordings from Peter Tosh, Burning Spear and, most famously, Bob Marley and the Wailers, whose ranks Barrett and his drum-playing brother Carlton joined ahead of the 1973 LP Catch a Fire.

“I’ve played before Bob, with Bob and after Bob, and along the way, I create a whole new concept of bass playing,” Barrett said in 2007. “That’s just my thing. That’s my destiny.”

Barrett (who adopted the “Family Man” nickname because he viewed his collaborators as kin, not because he went on to sire 41 children) was born in Kingston, Jamaica in 1946, four years ahead of Carlton, the family’s fifth and final child. Aston later recalled singing along to soul music on the radio before building his first bass guitar from scrap plywood, a curtain rod and an old ashtray; he acquired a Hofner 500/1 “Beatle” bass before he and Carlton joined the Hippy Boys behind singer Max Romeo.

Barrett made his debut as a session musician in 1968 when he cut the Uniques’ “Watch This Sound” for producer Bunny “Striker” Lee, and in the process invented the reggae bassline as we know it today. “I was improvising from the rocksteady feel, with a little tempo from the rocksteady and slowing it down from the ska, so the rhythm is in between the lines,” Barrett told Bass Player four decades later.

Producer Lee “Scratch” Perry took notice, and added the Barrett brothers to his house band, the Upsetters, for a series of echo-drenched recordings that pioneered dub, a reggae offshoot synonymous with its foundation-rattling rhythms. “Lee Perry get a hold of me by hearing of my new concept of bass playing,” Barrett recalled. “He was turning into a record producer, leaving from the old stable of [producer] Coxsone Dodd at Studio One. The first thing we actually did together was the drum-and-bass track called ‘Clint Eastwood,’ and that’s where dub was born. It was the first dub release not only in Jamaica, but globally.”

Family Man jettisoned the Hofner for a Fender Jazz Bass by the time the Wailers recorded Catch a Fire. “I was using acoustic amplifiers with the Fender. I had two 18-inch cabinets and two 4×15 cabinets,” Barrett said. “You need them that big to get that sound, because reggae music is the heartbeat of the people. It’s the universal language what carry that heavy message of roots, culture and reality. So the bass have to be heavy, and the drums have to be steady.”

Kinky Reggae (1973)

The Barrett brothers kick off “Kinky Reggae,” Catch a Fire’s ode to the temptations of a strange new city, with an easy mid-tempo groove filled out by Winston Wright’s organ accents. The Barretts don’t simply keep time on “Kinky Reggae,” however: they stretch and compress it, push it and pull it, sometimes venturing ahead of the beat and other times floating behind it — a telepathic approach to tempo made possible by the signature steadiness of Marley’s guitar rhythms. Isolate Barrett’s “Kinky Reggae” performance in KORD to fully appreciate the inventiveness of his contributions, like his use of triplets in the pre-chorus (under the “Ride on” lyrics); were it not for Marley’s charismatic vocals, the bass would undoubtedly serve as the song’s focal point.

Marley emerged as reggae’s most popular and influential performer in the wake of Catch of Fire, reeling off a series of now-classic songs like “I Shot the Sheriff” (a number-one pop hit for Eric Clapton in 1974, the same year Barrett was named the Wailers’ bandleader and musical arranger), “No Woman No Cry” (a highlight of 1975’s landmark Live!) and the human rights anthem “Get Up, Stand Up,” arguably the purest, most universal expression of the devoutly Rastafarian Marley’s political and spiritual ideals. But soon after the release of 1976’s Rastaman Vibration — the Wailers’ commercial breakthrough in the U.S., reaching the Top 50 of Billboard’s soul charts — Marley was the target of an assassination attempt, and in the attack’s aftermath, he and the Wailers decamped to London for 14 months to record 1977’s Exodus as well as its immediate follow-up, Kaya.

Exodus (1977)

The funky “Exodus,” Marley’s first single to earn widespread airplay on America’s Black radio stations, began as a studio jam, and stretches close to eight minutes in length — uncharted territory for reggae recordings. The song connects the Old Testament tale of Moses leading the Israelites out of Egypt to calls for Rastafarian repatriation, complete with the incantatory chorus “Exodus! Movement of Jah people!” The driving, militant beat established by Marley’s guitar underlines the urgency of his message: Carlton Barrett plays a classic four-on-the-floor bass drum pattern, contrasted with a mesmerizing display of syncopated upbeats on the snare and tom toms, while Family Man plays essentially the same repeating figure with slight variations.

- /songs/202142021AP205T

“The drum, it is the heartbeat, and the bass, it is the backbone,” Barrett proclaimed in 2007. “If the bass is not right, the music is gonna have a bad back, so it would be crippled.” (Mute all of the “Exodus” stems but the bass and drums to create your own Lee “Scratch” Perry-inspired dub version.)

Is This Love (1978)

Kaya pivoted from the political to the personal, highlighted by the slinky, sunkissed “Is This Love,” a paean to domestic bliss dedicated to Marley’s wife Rita, also a member of his backing vocal unit the I-Threes. “I wanna love you, and treat you right/I wanna love you, every day and every night,” Marley sings, an unabashedly romantic declaration that inspired critic Lester Bangs to dub him “the Barry White of Montego Bay” in a savage review of Kaya (“quite possibly the blandest set of reggae music I have ever heard”) published in Rolling Stone’s June 1, 1978 edition. Bangs was far from alone in dismissing the album: many critics took issue with its more introspective sensibilities and softer-edged production, and some even suggested Marley had sold out his political beliefs. “Me never like what politics really represent,” Marley told Hot Press around the time of Kaya’s release. “’Tis music. It can’t be political all the while.”

Credit Barrett’s warm, round basslines for making “Is This Love” swing; mute his performance in KORD to hear how suddenly flat and lifeless the song becomes in his absence. Both Marley and Family Man play with a triplet feel, but the bass is much busier, with swung 16th notes throughout, while Marley’s 12-string acoustic guitar is more judicious in its approach, leaving far more space. The result is a duet of fully-improvised interwoven lines that complement each other perfectly.

Apart from the Wailers, Barrett played on genre-defining sessions like Keith Hudson’s Pick a Dub, ex-Wailer Tosh’s Legalize It and Burning Spear’s Marcus Garvey. He also mentored bassist Robbie Shakespeare, one half of the prolific rhythm section and production duo Sly & Robbie. Following Marley’s May 11, 1981 death from acral lentiginous melanoma, Barrett continued to lead the Wailers on tour, remaining with the group even after Carlton Barrett’s 1987 murder. Aston Barrett retired from music in 2019; he died in Miami on Feb. 3, 2024, aged 77.

“Well… what can I say? He is the man. Just the way the man plays the bass, you know,” Shakespeare said in 2009. “There are gunfighters and there are gunfighters, seen? I can’t tell you nothing more. He is a master for me. I have had help and influences from other people, but I have to give it mostly to Family Man.”

KORD Interactive Playlists leverage the app’s stem player to explore pop music history in a whole new way. Each playlist supplies the technological capabilities and narrative context to fully appreciate the contributions of music’s unsung heroes: the virtuoso session players, producers, songwriters and arrangers behind the superstars.